Rabies and other lyssaviruses

Information about rabies disease, vaccines and recommendations for vaccination from the Australian Immunisation Handbook.

Recently added

This page was added on 06 June 2018.

Updates made

This page was updated on 18 December 2025. View history of updates

Vaccination for certain groups of people is funded by states and territories.

Overview

What

Rabies is a zoonotic disease caused by exposure to saliva or neural tissue from an animal infected with rabies virus or other lyssaviruses. Human exposure can occur through an animal scratch or bite that has broken the skin, or by direct contact of the virus with the mucosal surface of a person, such as nose, eye or mouth.

Who

Pre-exposure rabies vaccine is recommended for:

- people who have contact with bats

- people who travel to rabies-enzootic regions, based on a risk assessment

- laboratory workers who work with live lyssaviruses

Post-exposure rabies vaccine and, in some cases, human rabies immunoglobulin are recommended for anyone who has potentially been exposed to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses.

How

There are 4 options for administering pre-exposure prophylaxis, varying by schedule length, number of doses and route of administration. There is no preferential recommendation for choosing a schedule and route of administration. Consideration should include a person’s circumstance and personal preferences.

Post-exposure prophylaxis includes prompt wound management, and administration of rabies vaccine and, in some cases, human rabies immunoglobulin. The appropriate combination of these interventions and the number of vaccine doses depend on a risk assessment that takes into account the:

- extent of the exposure

- animal source of the exposure

- person’s immune status

- person’s previous vaccination history

Why

Rabies is almost always fatal. Australia is not a rabies-enzootic country. Exposure to classical rabies virus can occur from terrestrial animals and other mammals in rabies-enzootic countries. Bats anywhere in the world are a potential source of lyssaviruses and a potential risk for acquiring rabies, depending on how a person is exposed. Evidence of Australian bat lyssavirus infection has been identified in all 4 species of Australian fruit bats (flying foxes) and in several species of Australian insectivorous bats.

Recommendations

Vaccination before exposure to rabies virus and other lyssaviruses (pre-exposure prophylaxis)

-

Pre-exposure prophylaxis with rabies vaccine is recommended for:

- people who may receive bites or scratches from bats — these include bat handlers; veterinarians and veterinary nurses; wildlife officers, wildlife carers and zookeepers; wildlife researchers; and others who come into direct contact with bats in any country, including Australia

- research laboratory workers working with any live lyssavirus

- people who will be travelling to, or living in, rabies-enzootic areas — give pre-exposure prophylaxis after a risk assessment that considers the likelihood that the person will interact with animals and their access to emergency medical attention

Rabies vaccines can be given by the intramuscular or intradermal route. The intradermal route uses 0.1mL per dose of all vaccines. The intramuscular route uses 0.5mL for Verorab and 1.0mL for Rabipur.

The intradermal route may only be used by suitably qualified and experienced providers (eg travel medicine clinics). See Administration of vaccines. This route is only to be used for pre-exposure vaccination of immunocompetent people.

The intradermal route is an unlicensed (‘off-label’) route of administration. If intradermal rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis is considered, it is essential that:

- it is given by immunisation providers who have expertise in, and regularly practise, the intradermal technique, because incorrect administration may mean the person being vaccinated is not adequately protected

- it is not given to people who are immunocompromised, as the immune response may not be adequate1,2,3

- it is not given to people taking chloroquine, or other antimalarials that are structurally related to chloroquine (such as mefloquine or hydroxychloroquine), at the time of vaccination or within 1 month after vaccination, as this can reduce the immune response to intradermal rabies vaccine4

- the immunisation provider follows procedures for the use of a multidose vial and discards any remaining vaccine after 8 hours or at the end of the vaccination session, whichever occurs first

There are 4 options for administering pre-exposure prophylaxis, varying by schedule length, number of doses and route of administration. There is no preferential recommendation for choosing a schedule and route of administration. Consideration should include a person’s circumstance and personal preferences.

3-visit schedules

3-visit schedules

The recommended 3-visit pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule comprises 3 vaccine doses, given at days 0, 7 and 21–28. These can be given by either the intramuscular or intradermal route.

2-visit schedules

2-visit schedules

The recommended 2-visit pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule given by the intramuscular route comprises 2 vaccine doses, given as follows:

- 1 injection (1.0mL for Mérieux and Rabipur, 0.5mL for Verorab) on day 0

- 1 injection (1.0mL for Mérieux and Rabipur, 0.5mL for Verorab) on day 7

The recommended 2-visit pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule given by the intradermal route comprises 4 vaccine doses, given as follows:

- 2 x 0.1 mL injections given at different sites on day 0

- 2 x 0.1 mL injections given at different sites on day 7

Do not use 2-visit schedules in people who are immunocompromised, as the immune response may not be adequate.5

Do not use this 2-visit intradermal schedule in adults >50 years of age, because studies show that seroconversion is less likely to occur in this age group than in younger people.6,7

These 2-visit schedules provide short-term protection, particularly beneficial for travel to rabies-enzootic areas. If further protection is required after 1 year, antibody levels may no longer be adequate.8-10 A single intramuscular booster dose should be given 1 year after the 1st dose of pre-exposure prophylaxis, regardless of the administration route for the original pre-exposure prophylaxis course. An intramuscular booster dose of rabies vaccine should still provide adequate protection even if given more than 1 year after the 1st dose of pre-exposure prophylaxis.9,11,12,13

Booster doses

Booster doses

Booster doses of rabies vaccine are recommended for immunised people who have ongoing occupational exposure to lyssaviruses in Australia or overseas. See People with ongoing occupational exposure to lyssaviruses are recommended to receive booster doses of rabies vaccine.

Serological testing for people who received pre-exposure prophylaxis by the intradermal route

Serological testing for people who received pre-exposure prophylaxis by the intradermal route

If pre-exposure prophylaxis was received by the intradermal route, rabies antibody level should ideally be checked 2–4 weeks after finishing the pre-exposure course to ensure that VNAb (rabies virus neutralising antibody) levels are ≥0.5 IU per mL. Seek expert advice via state or territory health authorities or specialist immunisation clinics if the titre is <0.5 IU per mL.

If there will be insufficient time before travel for serological testing to be performed, the intramuscular route for vaccination should be preferred.

Serological testing for people who are immunocompromised

Serological testing for people who are immunocompromised

People who are immunocompromised should have their VNAb titres checked 2–4 weeks after the 3rd intramuscular dose of vaccine in a 3-visit 21-28 day pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule. Give a further dose if the titre is <0.5 IU per mL, and repeat serological testing. If the titre remains <0.5 IU per mL, seek advice via state or territory health authorities or specialist immunisation clinics.

View recommendation detailsRationale for pre-exposure prophylaxis

Rationale for pre-exposure prophylaxis

Pre-exposure prophylaxis simplifies how a potential subsequent exposure to rabies virus or Australian bat lyssavirus is managed because:

- the person needs fewer doses of rabies vaccine in the post-exposure phase

- the person does not need RIG (rabies immunoglobulin) unless they are severely immunocompromised

This is particularly important because RIG — either human (HRIG), equine (ERIG) or monoclonal RIG — can be difficult to obtain and is expensive, and its safety cannot be guaranteed in many rabies-enzootic developing countries. See also Vaccination after potential exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses (post-exposure prophylaxis).

-

People who will be travelling to, or living in, rabies-enzootic areas should have a risk assessment by a health professional that considers their likelihood of interacting with animals and access to emergency medical attention in that location. This is needed to guide the decision to give rabies vaccine as pre-exposure prophylaxis.

People likely to be exposed to potentially rabid terrestrial animals in rabies-enzootic areas should receive pre-exposure prophylaxis.

To reduce their risk of exposure to rabies virus and other lyssaviruses, advise travellers to rabies-enzootic regions as follows:

- Avoid close contact with wild and domestic animals — this is especially important for children.12-16

- Avoid contact with stray dogs or cats. Be vigilant when walking, running or cycling.

- Do not allow young children to feed, pat or play with animals. Young children’s height makes bites to the face and head more likely. Bites in these locations increase the risk of developing rabies and reduce the time to onset of disease. Parents travelling with children to rabies-enzootic areas should consider pre-exposure prophylaxis for younger children.

- Do not carry food, and do not feed or pat monkeys, even in popular areas around temples or markets where travellers may be encouraged to interact with monkeys. In particular, do not focus on monkeys carrying their young, as they may feel threatened and bite suddenly.

- Avoid contact with bats anywhere in the world, including Australia. Only people who are appropriately vaccinated and trained should handle bats. If bats must be handled, follow safety precautions, such as wearing protective gloves and clothing.

- Know what to do if an animal bites or scratches14-18 — travellers should be educated about first aid treatment for rabies exposures, regardless of whether they have received the vaccine.

Note that bites have occurred in travellers who did not initiate any contact with animals, including people taking photos of an animal.19

For pre-exposure prophylaxis schedules, see People who work with bats, laboratory workers who work with live lyssaviruses and some people who travel to rabies-enzootic areas are recommended to receive rabies vaccine as pre-exposure prophylaxis.

View recommendation details -

Booster doses of rabies vaccine are recommended for immunised people who have ongoing occupational exposure to lyssaviruses in Australia or overseas.9,11,21-23 See Figure. Booster algorithm for people at ongoing risk of exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses. These include the following:

- People who work with live lyssaviruses in research laboratories should have VNAb (rabies virus neutralising antibody) titres measured every 6 months. If the titre is <0.5 IU per mL, they should receive a single intramuscular booster dose. People who are immunocompromised should have their VNAb titre measured 2–4 weeks after the booster dose. If the titre is <0.5 IU per mL, they should receive another booster dose. There is no need for serological testing after this additional dose. Laboratory staff at ongoing risk should continue to check their VNAb titres every 6 months.

- People with exposure to bats in Australia or overseas, or people who are likely to be exposed to potentially rabid terrestrial mammals overseas should have a single intramuscular booster dose 1 year after their 1st dose of rabies vaccine pre-exposure prophylaxis (or 1 year after their 1st dose of post-exposure prophylaxis if they had a category II or III exposure before receiving pre-exposure prophylaxis; see Table. Lyssavirus exposure categories). These people should have VNAb titres measured every 3 years after that. If their VNAb titre is <0.5 IU per mL, they should have a further single intramuscular booster dose. Alternatively, after the 1st booster dose, they can have a further single intramuscular booster dose every 3 years without determining the VNAb titre. An intramuscular booster dose of rabies vaccine should still provide adequate protection even if given more than 1 year after the 1st dose of pre-exposure prophylaxis.9,11

Always give booster doses of rabies vaccine by the intramuscular route. Never use the intradermal route to administer booster doses.

To determine whether a person should receive a booster dose of rabies vaccine because their VNAb titre falls below 0.5 IU per mL, consider:

- their anticipated risk of exposure — that is, whether they are routinely handling sick animals or rabies reservoir species in rabies-enzootic areas

- their health status, such as level of immunocompromise (see Table. Types of medical conditions and immunosuppressive therapy and associated levels of immunocompromise) or a history of poor vaccine response

- their timely access to vaccination for post-exposure prophylaxis if they are exposed

View recommendation detailsFigure. Booster algorithm for people at ongoing risk of exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses

Show description of image

IU = international units; PEP = post-exposure prophylaxis; PrEP = pre-exposure prophylaxis

This flowchart helps to decide if people at ongoing occupational risk need booster doses of rabies vaccine.

For laboratory staff at risk, perform serological testing every 6 months.

For veterinary workers, people who handle bats or may need to handle bats, and people who have ongoing exposure to potentially rabid terrestrial mammals in rabies-enzootic countries, give a single intramuscular booster dose 1 year after pre-exposure prophylaxis. Then perform serological testing or give a booster dose every 3 years from receipt of the 1-year booster dose.

After serological testing, for those who have a virus neutralising antibody titre of at least 0.5 IU/mL, no further action is needed until either there is further exposure (then give post-exposure prophylaxis as per rabies or bat lyssavirus post-exposure algorithms, unless exposure occurs within 3 months of receiving complete post-exposure prophylaxis, when no immediate vaccination is required) or the next serological testing period elapses (then perform serology).

For those with a virus neutralising antibody titre of <0.5 IU/mL, give a single intramuscular booster dose for immunocompetent people. For immunocompromised people, give a single intramuscular booster dose then check serology after 2–4 weeks. If the antibody titre is <0.5 IU/mL, give another booster dose. If further exposure occurs, give post-exposure prophylaxis as per the terrestrial animal post-exposure algorithm or the bat post-exposure algorithm.

Vaccination after potential exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses (post-exposure prophylaxis)

-

Post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies virus and other lyssavirus exposures comprises:

- prompt wound management

- rabies vaccine

- HRIG (human rabies immunoglobulin)

The appropriate combination of these components depends on a detailed risk assessment, including determining the:

- type of exposure (see Table. Lyssavirus exposure categories)

- animal source of the exposure

- person’s immune status

- person’s previous vaccination history

Post-exposure prophylaxis must include wound management

Post-exposure prophylaxis must include wound management

Wound management is a vital step after a potential exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses. To help prevent rabies transmission:

- immediately and thoroughly wash all bite wounds and scratches with soap and water

- apply a virucidal preparation such as povidone-iodine solution

Avoid suturing a bite from a potentially rabid animal. Instead, clean, debride and infiltrate the wound well with rabies immunoglobulin. See either:

- Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures, or

- Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures

Also consider whether the wound could be infected with pathogens such as Clostridium tetani, and take appropriate measures (see Tetanus).

Assess all potential exposures from a terrestrial animal in a rabies-enzootic area, or from a bat anywhere in the world

Assess all potential exposures from a terrestrial animal in a rabies-enzootic area, or from a bat anywhere in the world

Assess all exposures to terrestrial mammals (in rabies-enzootic countries) and bats (in any country) for potential classical rabies virus transmission.

There are 2 different post-exposure prophylaxis management algorithms, depending on whether the lyssavirus exposure was:

- from a terrestrial animal in a rabies-enzootic country — see Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures, or

- from a bat (in Australia or overseas) — see Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures

These 2 algorithms are different because:24

- the risk from wounds from bats is often hard to determine — wounds from bat bites and scratches are usually smaller than other animal bites

- superficial wounds from bats are more likely to result in human infection than superficial wounds from terrestrial animals

Make every effort to have the animal tested for lyssaviruses after a potential human exposure, to avoid unnecessary post-exposure prophylaxis. For bites to the head and neck, give post-exposure prophylaxis as soon as possible and preferably less than 48 hours after exposure, even if the animal has been sent for testing. Assess the risk of rabies after exposure to both live and dead animals. A study in mice showed that rabies virus remained viable in brain tissue from decomposing carcasses for:25

- up to 3 days in bodies kept at 25°C to 35°C

- up to 18 days in bodies kept at lower temperatures

Give post-exposure prophylaxis that is appropriate for the category and source of exposure, even if there was a considerable delay in reporting the incident. See Table. Lyssavirus exposure categories.

However, a person does not need post-exposure prophylaxis if they present ≥15 days after being bitten or scratched by a domestic pet in a rabies-enzootic country and it is known that the animal is healthy ≥15 days after the exposure.

Contact your state or territory health authority about any potential exposures. They can help conduct a detailed risk assessment and advise on management. See also Public health management.

Table. Lyssavirus exposure categoriesExposure category Description Post-exposure prophylaxis management Category I: no exposure - Touching or feeding animals

- Animal licks on intact skin

- Exposure to animal blood, urine or faeces

No prophylaxis required if contact history is reliable Category II: exposure - Nibbling of uncovered skin

- Minor scratches or abrasions without bleeding

See the following, depending on the circumstances:

Category III: severe exposure - Single or multiple transdermal bites or scratches

- Contamination of mucous membrane or broken skin with saliva from animal licks

- Exposures due to direct contact with bats

See the following, depending on the circumstances:

View recommendation detailsPotential exposure to Australian bats

Potential exposure to Australian bats

The type of potential exposure to Australian bats may be difficult to categorise. This could be because a person is unaware of, or unable to communicate about, the exposure — for example:

- a person with a developmental disability

- an intoxicated person

- a child

- a person who has been sleeping in a confined space with a bat present

If possible, and without placing others at risk of exposure, keep the bat and arrange to have it tested for ABLV (Australian bat lyssavirus).

After wound management (see Post-exposure prophylaxis must include wound management), withhold giving HRIG and rabies vaccine if the bat’s ABLV status will be available within 48 hours of the exposure. If the bat’s ABLV status will not be available within 48 hours, start the appropriate post-exposure prophylaxis as soon as possible. For bites to the head and neck, give post-exposure prophylaxis as soon as possible and preferably less than 48 hours after exposure, even if the animal has been sent for testing.

Follow the bat exposure algorithm in Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures.

If the bat is negative for ABLV, stop the post-exposure prophylaxis.

-

After managing the wound, give rabies vaccine with or without HRIG (human rabies immunoglobulin), depending on the category and source of exposure. See:

- Table. Vaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure category

- Table. Unvaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure category

- Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures

- Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures

If a person’s vaccination status is uncertain because documentation showing a full course of rabies vaccine is not available, give the full post-exposure prophylaxis regimen.

Vaccine given intradermally for pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis can be considered previous vaccination.

Table. Vaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure categoryVaccinated people have evidence of a completed recommended pre-exposure or post-exposure prophylaxis regimen at any time in the past, or have a documented VNAb (rabies virus neutralising antibody) titre of >0.5 IU per mL at any time in the past. For those with a history of partial immunisation, see Incomplete pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule.

Immune status Exposure category HRIG Dose 1 (day 0) Dose 2 (day 3) Dose 3 (day 7) Dose 4 (day 14) Dose 5 (day 28) Immunocompetent Any category II or III Not needed Yes Yes Not needed Not needed Not needed Mildly or moderately immunocompromised Any category II or III Not needed Yes Yes Not needed Not needed Not needed Severely immunocompromised Any category II or III Not needed Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes HRIG = human rabies immunoglobulin

Deviations of a few days from this schedule are probably unimportant.27

For defining the level of immunocompromise, see Definitions and Table. Types of medical conditions and immunosuppressive therapy and associated levels of immunocompromise in Vaccination for people who are immunocompromised.

Table. Unvaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure categoryImmune status Exposure category HRIG Dose 1 (day 0) Dose 2 (day 3) Dose 3 (day 7) Dose 4 (day 14) Dose 5 (day 28) Immunocompetent Category II terrestrial animals Not needed Yes Yes Yes Yes Not needed Category II bats and any category III Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Not needed Mildly or moderately immunocompromised Any category II or III Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Severely immunocompromised Any category II or III Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes HRIG = human rabies immunoglobulin

Deviations of a few days from this schedule are probably unimportant.27

For defining the level of immunocompromise, see Definitions and Table. Types of medical conditions and immunosuppressive therapy and associated levels of immunocompromise in Vaccination for people who are immunocompromised.

Administration of rabies vaccine for post-exposure prophylaxis by the intradermal route is not recommended.

No clinical trial has assessed the efficacy of rabies vaccine, but the rationale supporting a 4-dose schedule in immunocompetent people is based on numerous studies.27-29 There have been no reported cases in Australia or internationally of vaccine failure in people who have been potentially exposed and have received a complete course of post-exposure prophylaxis.30

Incomplete pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule

Incomplete pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule

People who have only received 1 dose previously as pre-exposure prophylaxis require 4 doses as post-exposure prophylaxis (similar to those who are unvaccinated):

- If the single dose was given intramuscularly within the 12 months before exposure, no HRIG is required.

- If the single dose was given more than 12 months before exposure, HRIG is required.

- If the single dose was given intradermally, HRIG is required, regardless of when it was given.

People with any level of immunocompromise who received an incomplete pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule should receive post-exposure prophylaxis as for unvaccinated people, including HRIG.

People who are immunocompromised

People who are immunocompromised

Where possible, stop any immunosuppressive therapy (including corticosteroids) while giving post-exposure prophylaxis. Such treatment may interfere with the development of a protective response from the vaccine. Consult the person’s treating specialist to discuss the feasibility of this.

Measure the VNAb titre 2–4 weeks after the last dose. If the titre is <0.5 IU per mL, give another dose. Repeat the serological testing 2–4 weeks after this dose. If the titre is still <0.5 IU per mL, seek advice via state or territory health authorities.

People who are severely immunocompromised should always receive a dose of rabies immunoglobulin in addition to rabies vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis, even if they have previously received rabies vaccine.

For defining the level of immunocompromise, see Definitions and Table. Types of medical conditions and immunosuppressive therapy and associated levels of immunocompromise in Vaccination for people who are immunocompromised.

Repeat rabies exposure

Repeat rabies exposure

People with a repeat exposure within 3 months of completing previous post-exposure prophylaxis do not need any further vaccine doses, HRIG and only need wound management (regardless of immune status).

View recommendation detailsUse of human rabies immunoglobulin

Use of human rabies immunoglobulin

Some people with a potential exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses are recommended to receive HRIG in addition to rabies vaccine as post-exposure prophylaxis. See:

- Table. Lyssavirus exposure categories

- Table. Vaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure category

- Table. Unvaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure category

- Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures

- Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures

Where indicated, give a dose of HRIG as soon as possible, and within 7 days (168 hours), after the 1st vaccine dose. Do not give HRIG if more than 7 days (168 hours) have passed since the 1st vaccine dose.

HRIG provides localised anti-rabies antibody protection while the person responds to the rabies vaccine. For information on how to administer HRIG, see Vaccines, dosage and administration.

HRIG is not recommended in people who:

- received the 1st dose of vaccine more than 7 days (168 hours) before presenting for HRIG — that is, more than 7 days (168 hours) have passed since they received the 1st dose of vaccine

- present for medical care more than 12 months after the potential exposure

- have a documented history of at least 2 doses of rabies vaccine from either pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis, as this may suppress the memory response and circulating VNAb; this excludes people who are severely immunocompromised, who always need HRIG (see Table. Vaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure category, and Table. Unvaccinated people: post-exposure rabies prophylaxis based on immune status and exposure category)

- have a documented history of 1 dose of rabies vaccine given by the intramuscular route, within the 12 months before exposure

- have documented evidence of VNAb titres >0.5 IU per mL at any time in the past

These people should receive rabies vaccine only.

Data are limited on the effectiveness of rabies vaccine and HRIG as post-exposure prophylaxis against infection with lyssaviruses other than classical rabies virus. However, the available animal data and clinical experience support their use.32-37

-

Australians travelling overseas who are exposed to a potentially rabid animal (including bats from any country) may receive post-exposure prophylaxis using cell culture–derived vaccines and schedules that are not used in Australia.

If the person received an older nerve tissue–derived rabies vaccine, do not regard these doses as valid. This is a very rare circumstance. See Table. Completing post-exposure prophylaxis in Australia that started overseas.

If a person received either a chick embryo–derived or a cell culture–derived vaccine overseas, they are recommended to continue the standard post-exposure prophylaxis regimen in Australia with either human diploid cell vaccine or purified chick embryo cell vaccine. See Interchangeability of rabies vaccines.

In general, cell culture–derived vaccines are acceptable if they contain at least 2.5 IU of rabies virus per dose and there is scientific literature demonstrating an acceptable post-exposure antibody response (rabies virus neutralising antibody ≥0.5 IU per mL). See Table. Rabies vaccines available globally, and compatibility with vaccines registered in Australia.

Table. Rabies vaccines available globally, and compatibility with vaccines registered in AustraliaRabies vaccine Vaccine information Compatible Human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV) Imovax, Sanofi Pasteur SA

Kanghua Rabies, Chengdu Kanghua Biological Products China

Yes Purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV) RabAvert, GSK

Vaxirab-N, Cadila Healthcare India

Yes Purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV) RABIVAX-S, Serum Institute India

SPEEDA, Chengda Bio China

Abhayrab (except if administered in India*), Human Biologicals Institute India

Indirab, Bharat Biotech India

Yes Purified duck embryo vaccine (PDEV) Lyssavac, Cadila Healthcare India

Vaxirab, Cadila Healthcare India

Yes Primary Syrian hamster kidney cell vaccine (PHKCV) Local producers in China Yes Baby hamster kidney cell vaccine (BHKV) Kokav, Russia Yes Recombinant nanoparticle-based rabies G protein virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine ThRabis, Cadila Pharmaceuticals India No Suckling mouse brain vaccine (SMBV) Used in South America No Nervous tissue vaccine (sheep, goat) Used in Asia, Ethiopia and Argentina No * Counterfeit Abhayrab® vaccine (batch number KA24014) has been identified in India. See ATAGI statement: Counterfeit Rabies vaccine (Abhayrab®) reported in India: Guidance for travellers and healthcare providers (11 January 2026).

View recommendation detailsIntramuscular dosing schedules for post-exposure rabies vaccination for people who have not been vaccinated for rabies that are approved by the World Health Organization include:

- Zagreb regimen — 2 doses on day 0, doses on days 7 and 21 (annotated as 2-0-1-0-1)

- Essen regimen — doses given on days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 28 or 30 (annotated as 1-1-1-1-1)

- modified Essen regimen — doses given on days 0, 3, 7 and 14-28 (annotated as 1-1-1-1-0)

Intradermal dosing regimens for post-exposure rabies vaccination that are approved by the World Health Organization include:

- Institut Pasteur du Cambodge (IPC) regimen — 2 doses on days 0, 3 and 7 (annotated as 2 2 2 0 0)

- updated Thai Red Cross (TRC) regimen — 2 doses on days 0, 3, 7 and 28 (annotated as 2 2 2 0 2)

A person is recommended to receive HRIG (human rabies immunoglobulin) in Australia if:

- it is indicated for the type of exposure and the person’s immune status (see Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures or Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures) and

- the potential exposure was within the past 12 months and

- they started post-exposure prophylaxis overseas but HRIG or ERIG (equine rabies immunoglobulin) was not given and

- they received the 1st post-exposure prophylaxis vaccine dose within the past 7 days (168 hours). HRIG should be given in a different limb to the vaccine.

If the person in Australia had their 1st post-exposure prophylaxis dose more than 7 days ago, they should not receive HRIG. However, they should still complete the appropriate number of remaining rabies vaccine doses.

For these and other scenarios, Table. Completing rabies post-exposure prophylaxis in Australia that started overseas outlines the most common post-exposure prophylaxis regimens that may be started overseas and the recommended schedule to complete post-exposure prophylaxis in Australia.

Advise travellers that, if they start post-exposure prophylaxis while overseas, they must request a post-exposure prophylaxis certificate from the vaccination centre, and obtain or record the following information (preferably in English):

- the contact details for the clinic attended (telephone and email address)

- the batch and source of RIG (rabies immunoglobulin) used (some countries may use ERIG or monoclonal RIG rather than HRIG)

- the volume of RIG administered

- the type of cell culture vaccine used

- the vaccine batch number

- the number of vials used

- the route of vaccine administration

- the date and time of administration of RIG and/or vaccine

These details help inform decisions about how to complete post-exposure prophylaxis when the traveller returns home.

-

Pregnant or breastfeeding women are recommended to receive rabies vaccine and human rabies immunoglobulin, if required, after a potential exposure to rabies virus, Australian bat lyssavirus or another bat lyssavirus.37,38 See Table. Vaccines that are not routinely recommended in pregnancy: inactivated viral vaccines in Vaccination for women who are planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding.

View recommendation details

Tables & figures

See also Table. Lyssavirus exposure categories.

These scenarios assume the person had not received pre-exposure prophylaxis before the exposure. For more details, see Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures or Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: bat exposures.

| Overseas scenario | Rabies vaccine schedule (with or without HRIG) in Australia |

|---|---|

| Person received nerve tissue–derived vaccine |

|

| Use of vaccine or RIG is unsure or unknown, or documentation is poor. |

|

| Person is immunocompromised, and vaccines were administered intradermally |

|

| Scenario is well documented. Person received 2 vaccine doses given intradermally on day 0 (IPC/TRC regimens). RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine |

|

| Scenario is well documented. Person received 2 vaccine doses given intradermally on each of day 0 and day 3 (IPC/TRC regimens). RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine |

|

| Scenario is well documented. Person received 2 vaccine doses given intradermally on each of day 0, day 3 and day 7 (IPC/TRC regimens). RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine |

|

| Scenario is well documented. Person received a vaccine dose given intramuscularly on each of day 0 and day 3 (Essen/modified Essen regimen). RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine |

|

| Person received 2 vaccine doses given intramuscularly on day 0 (Zagreb regimen). RIG (equine or human) may or may not have been administered at same time as 1st dose of vaccine |

|

| Footnotes: HRIG = human rabies immunoglobulin; IPC/TRC = Institut Pasteur du Cambodge/updated Thai Red Cross; PEP = post-exposure prophylaxis; RIG = rabies immunoglobulin | |

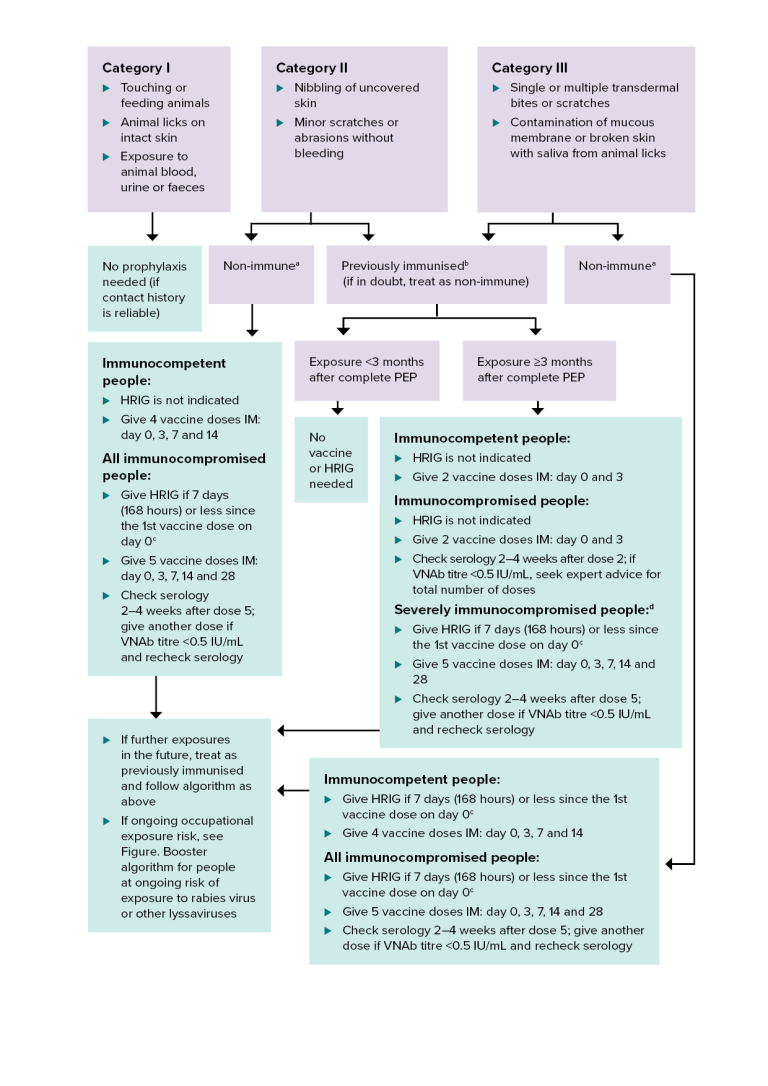

Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: terrestrial animal exposures

HRIG = human rabies immunoglobulin; IM = intramuscularly; IU = international units; PEP = post-exposure prophylaxis; VNAb = virus neutralising antibody

a Non-immune — person who has never received pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis with rabies vaccine, or has had an incomplete (<2 doses) primary vaccination course.

b Previously immunised — documentation of at least 2 doses of pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis rabies vaccine, regardless of the time since the last dose was given. It may be either a completed primary pre-exposure course or a post-exposure course. It includes people who had subsequent boosters, or who have documented rabies VNAb titres ≥0.5 IU/mL. For more details, see Incomplete pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule.

c Give HRIG in a different limb to the vaccine.

d For defining the level of immunocompromise, see Definitions and Table. Types of medical conditions and immunosuppressive therapy and associated levels of immunocompromise in Vaccination for people who are immunocompromised.

This algorithm gives guidance on post-exposure prophylaxis after potential exposure to lyssaviruses from a terrestrial animal in a rabies-enzootic area.

There are 3 categories of rabies exposure:

- Category 1. Touching or feeding animals, animal licks on intact skin, or exposure to animal blood, urine or faeces.

- Category 2. Animal nibbling of uncovered skin, or minor scratches or abrasions without bleeding.

- Category 3. Single or multiple transdermal bites or scratches; contamination of mucous membrane or broken skin with saliva from animal licks.

Category 1 exposure does not require any prophylaxis if the contact history is reliable.

Category 2 exposure in a non-immune person (see note a). For immunocompetent people, HRIG is not indicated; give 4 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7 and 14. For all immunocompromised people with a category 2 exposure, give HRIG if 7 days (168 hours) or less since the 1st vaccine dose on day 0 (see note c); give 5 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28; check serology 2–4 weeks after dose 5; give another dose if VNAb titre is <0.5 IU/mL and recheck serology.

Category 2 or 3 exposure in a person who has been previously immunised (see note b; if in doubt, treat as non-immune). If exposure is <3 months after complete post-exposure prophylaxis, no vaccine or HRIG is needed. If exposure is 3 months or longer after complete post-exposure prophylaxis, vaccination is required. For immunocompetent people, HRIG is not indicated; give 2 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0 and 3. For immunocompromised people, HRIG is not indicated; give 2 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0 and 3; check serology 2–4 weeks after dose 2; if VNAb titre is <0.5 IU/mL, seek expert advice for total number of doses. For severely immunocompromised people (see note d), give HRIG if 7 days (168 hours) or less since the 1st vaccine dose on day 0 (see note c); give 5 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28; check serology 2–4 weeks after dose 5; give another dose if VNAb titre is <0.5 IU/mL and recheck serology.

Category 3 exposure in a non-immune person (see note a). For immunocompetent people, give HRIG if 7 days (168 hours) or less since the 1st vaccine dose on day 0 (see note c); give 4 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7 and 14. For all immunocompromised people, give HRIG if 7 days (168 hours) or less since the 1st vaccine dose on day 0 (see note c); give 5 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28; check serology 2–4 weeks after dose 5; give another dose if VNAb titre is <0.5 IU/mL and recheck serology.

For all exposure groups, if there are further exposures in the future, treat as previously immunised and follow the algorithm as above. If there is ongoing occupational exposure risk, see Figure. Booster algorithm for people at ongoing risk of exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses.

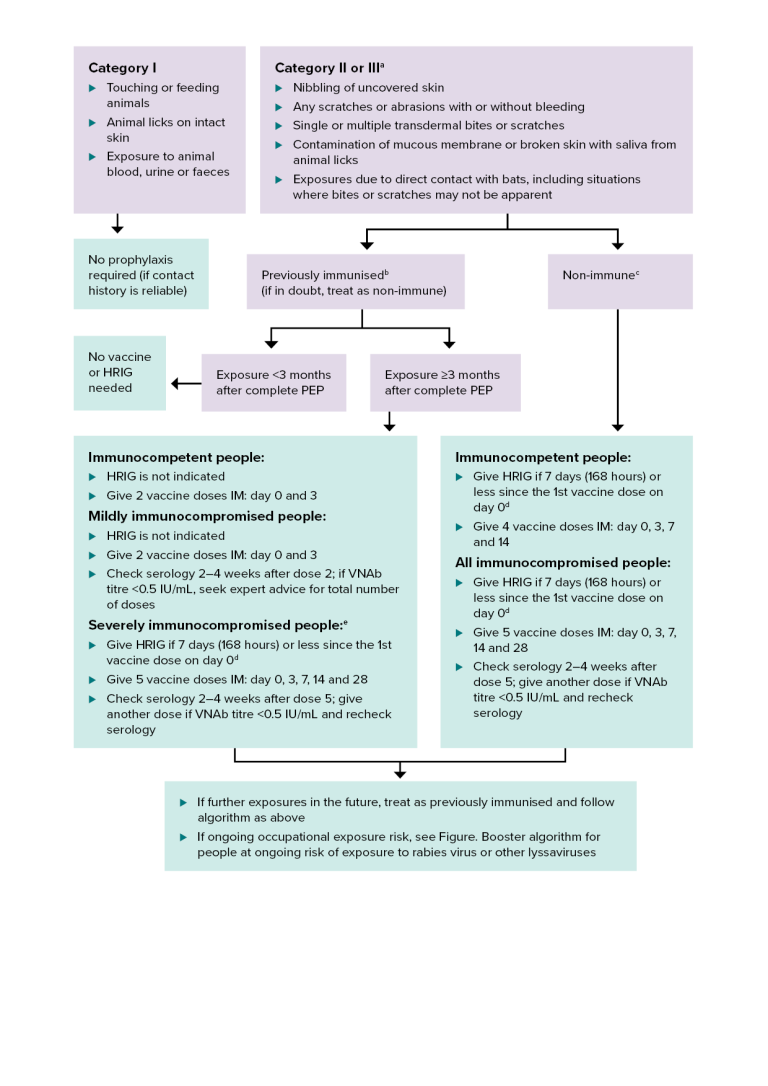

Figure. Rabies post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP): bat exposures

HRIG = human rabies immunoglobulin; IM = intramuscularly; PEP = post-exposure prophylaxis; VNAb = virus neutralising antibody

a Includes direct contact with bats in situations where the exposure may be difficult to categorise because a person does not know or cannot communicate if or how an exposure to a bat has occurred. Some bats have small teeth and claws, so bites or scratches may not be apparent.

b Previously immunised — documentation of at least 2 doses of pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis rabies vaccine, regardless of the time since the last dose was given. It may be either a completed primary pre-exposure course or a post-exposure course. It includes people who had subsequent boosters, or who have documented rabies VNAb titres ≥0.5 IU/mL. For more details, see Incomplete pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule.

c Non-immune — person who has never received pre- or post-exposure rabies vaccine, or has had an incomplete (<2 doses) primary vaccination course.

d Give HRIG in a different limb to the vaccine.

e For defining the level of immunocompromise, see Definitions and Table. Types of medical conditions and immunosuppressive therapy and associated levels of immunocompromise in Vaccination for people who are immunocompromised.

This algorithm gives guidance on post-exposure prophylaxis after potential exposure to lyssaviruses from bats in Australia or overseas.

There are 3 categories of exposure to lyssaviruses from bats:

- Category 1. Touching or feeding animals, animal licks on intact skin, or exposure to animal blood, urine or faeces.

- Category 2 or 3. (see note a) Animal nibbling of uncovered skin; any scratches or abrasions with or without bleeding; single or multiple transdermal bites or scratches; contamination of mucous membrane or broken skin with saliva from animal licks; or exposures due to direct contact with bats, including situations where bites or scratches may not be apparent.

Category 1 does not require any prophylaxis if the contact history is reliable.

Category 2 or 3 exposure in people who have been previously immunised (see note b; if in doubt, treat as non-immune). If exposure is <3 months after complete post-exposure prophylaxis, no vaccine or HRIG is needed. If exposure is 3 months or longer after complete post-exposure prophylaxis, vaccination is required. For immunocompetent people, HRIG is not indicated; give 2 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0 and 3. For mildly immunocompromised people, HRIG is not indicated; give 2 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0 and 3; check serology 2–4 weeks after dose 2; if VNAb titre is <0.5 IU/mL, seek expert advice for total number of doses. For severely immunocompromised people (see note e), give HRIG if 7 days (168 hours) or less since the 1st vaccine dose on day 0 (see note d); give 5 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28; check serology 2–4 weeks after dose 5; give another dose if VNAb titre is <0.5 IU/mL and recheck serology.

Category 2 or 3 exposure in a non-immune person (see note c). For immunocompetent people, give HRIG if 7 days (168 hours) or less since the 1st vaccine dose on day 0 (see note d); give 4 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7 and 14. For all immunocompromised people, give HRIG if 7 days (168 hours) or less since the 1st vaccine dose on day 0 (see note d); give 5 vaccine doses intramuscularly on days 0, 3, 7, 14 and 28; check serology 2–4 weeks after dose 5; give another dose if VNAb titre is <0.5 IU/mL and recheck serology.

For all exposure groups, if there are further exposures in the future, treat as previously immunised and follow the algorithm as above. If there is ongoing occupational exposure risk, see Figure. Booster algorithm for people at ongoing risk of exposure to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses.

Vaccines, dosage and administration

Rabies vaccines available in Australia

The Therapeutic Goods Administration website provides product information for each vaccine.

See also Vaccine information and Variations from product information for more details.

Rabies vaccines

-

Sponsor:SeqirusAdministration route:Intramuscular injection

Registered for use in people of any age.

PCECV — purified chick embryo cell vaccine

Lyophilised powder in a monodose vial with 1.0 mL distilled water as diluent.

Each 1.0 mL reconstituted dose contains:

- ≥2.5 IU inactivated rabies virus

Also contains traces of:

- neomycin

- chlortetracycline

- trometamol

- β-propiolactone

- monopotassium glutamate

- amphotericin B

May contain traces of:

- bovine gelatin

- egg protein

For Product Information and Consumer Medicine Information about Rabipur Inactivated Rabies Virus vaccine visit the Therapeutic Goods Administration website.

View vaccine details -

Sponsor:Sanofi-Aventis AustraliaAdministration route:Intradermal, Intramuscular injection

Registered for use in people of any age.

PVRV — purified Vero cell rabies vaccine

Lyophilised powder in a monodose vial with separate diluent.

Each 0.5 mL reconstituted dose contains:

- 3.25 IU inactivated rabies virus

- maltose

- 20% albumin solution

- Basal Medium Eagle, includes 4.1 µg phenylalanine

- sodium chloride

Also contains traces of:

- hydrochloric acid and/or sodium hydroxide

May contain traces of:

- neomycin

- streptomycin

- polymyxin

For Product Information and Consumer Medicine Information about Verorab Inactivated Rabies Virus Vaccine visit the Therapeutic Goods Administration website.

View vaccine details

Dose and route

The dose of rabies vaccine for pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis is 1.0 mL for Rabipur inactivated rabies virus vaccine and 0.5mL for Verorab inactivated rabies virus vaccine when given by intramuscular injection. This dose is the same for infants, children and adults.

The dose of all rabies vaccines for pre-exposure prophylaxis is 0.1 mL given by intradermal injection. This dose is the same for infants, children and adults. The intradermal route should only be used by suitably qualified and experienced providers. If giving rabies vaccine by the intradermal route, the total dose can be used for more than one person during a single vaccination session. Any remaining vaccine should be discarded at the end of the session. See Administration of vaccines.

Rabies vaccine should be given in the deltoid area, because VNAb (rabies virus neutralising antibody) titres may be lower if given in other sites. Infants <12 months of age are recommended to receive the rabies vaccine in the anterolateral aspect of the thigh. The ventrogluteal site is an acceptable alternative for infants. See Administration of vaccines.

Do not give rabies vaccine in the buttock, because post-exposure prophylaxis can fail when vaccine is given in this area.24

Co-administration with other vaccines

Rabies vaccines can be co-administered with other vaccines, using separate injection sites.

Human rabies immunoglobulin

HRIG (human rabies immunoglobulin) supplied in single-use vials containing 2 mL or 10 mL.

Each 1.0 mL contains:

- 150 IU rabies immunoglobulin (from human plasma)

- Glycine

- Water for injection

- Sodium hydroxide (for pH adjustment)

The dose of HRIG (human rabies immunoglobulin) is 20 IU per kilogram of body mass. This is the same for infants, children and adults.

People who need HRIG should receive it at the same time as the 1st dose (day 0) of rabies vaccine. Give HRIG in a different limb to the vaccine.

Do not give HRIG if it has been more than 7 days (168 hours) since the 1st dose of rabies vaccine. This is because HRIG may interfere with the immune response to the vaccine. For more details, see Recommendations.

In exceptional circumstances, such as during product shortages, other HRIG products may be available for use in Australia.

State and territory public health authorities can advise on using HRIG products. See also Public health management.

Infiltrating wounds with HRIG

HRIG must be infiltrated in and around all wounds using as much of the calculated dose as possible.

Any remaining HRIG that cannot safely be infiltrated in and around the wound should be given intramuscularly at a site away from the rabies vaccine injection site. Depending on the volume, this could be in the alternative deltoid, lateral thigh or gluteal muscle.

The HRIG dose should all be given intramuscularly if there is no obvious wound or site to infiltrate — for example, for mucous membrane exposures.

If the wounds are severe and the calculated volume of HRIG is not enough to completely infiltrate all wounds (such as extensive dog bites in a young child), dilute the HRIG in saline to make up an adequate volume to carefully infiltrate all wounds.

Wounds to fingers and hands may be small, especially if the wounds are from bats. Infiltrating these wounds with HRIG is likely to be both technically difficult and painful for the recipient.39 However, because fingers and hands have extensive nerve supply,40-42 it is important to infiltrate as much of the calculated dose of HRIG as possible using either a 25 or 26 gauge needle.

To avoid compartment syndrome, infiltrate the HRIG very gently. It should not cause the adjacent finger tissue to go pale or white. It may be necessary to give a ring block using a local anaesthetic.39

Interchangeability of rabies vaccines

It is preferable to use the same brand of vaccine for the entire course. However, a course of pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis can be completed with an alternative rabies cell culture–derived vaccine if necessary, if the vaccine is endorsed by the World Health Organization (also known as ‘pre-qualified’). If a person received a chick embryo–derived or cell culture–derived vaccine overseas, they are recommended to continue the standard post-exposure prophylaxis regimen in Australia with a registered Australian vaccine.

Various international vaccine advisory groups state that rabies cell culture–derived vaccines are interchangeable. This is supported by similarities in:

- tissue culture vaccine production methods

- antibody responses

- adverse reactions after vaccination

A study specifically assessed the interchangeability of human diploid cell vaccine and purified chick embryo cell vaccine. 165 people were randomised to receive rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis (days 0, 7 and 21–28) using either human diploid cell vaccine or purified chick embryo cell vaccine.43 Each group received 1 or 2 booster doses of purified chick embryo cell vaccine 1 year after the pre-exposure prophylaxis doses. The booster dose resulted in an anamnestic response (geometric mean titre several orders of magnitude >0.5 IU per mL) in all participants by day 7. This happened regardless of the vaccine that was used for the primary course. It is expected that this response would be similar with other rabies cell culture–derived vaccines.

Contraindications and precautions

Contraindications

There are no absolute contraindications to use of either rabies vaccine or human rabies immunoglobulin as post-exposure prophylaxis in people who have potentially been exposed to rabies virus or other lyssaviruses. This is because rabies is almost always lethal.

Precautions

People with egg allergy

People with a history of anaphylaxis or severe allergic reaction to eggs or egg proteins should not receive purified chick embryo cell vaccine. They should receive human diploid cell vaccine or purified Vero cell vaccine instead.

See also Adverse events.

Adverse events

Cell culture–derived vaccines are generally well tolerated. A large study reported the following adverse events after human diploid cell vaccine was administered to adults:44

- sore arm (in 15–25% of vaccine recipients)

- headache (in 5–8%)

- malaise or nausea, or both (in 2–5%)

- allergic oedema (in 0.1%)

Similar adverse event profiles have been reported for the purified chick embryo cell vaccine and the purified Vero cell rabies vaccine.45,46

These reactions occur at the same rates in children.47-53

Anaphylaxis and allergic reactions

Although anaphylaxis after receiving human diploid cell vaccine is rare (approximately 1 per 10,000 vaccinations), around 6% of people may have an allergic reaction after a booster dose. The reactions typically occur 2–21 days after the booster dose, and may include:44

- generalised urticaria

- arthralgia

- arthritis

- oedema

- nausea

- vomiting

- fever

- malaise

These reactions are not life-threatening. They have been attributed to the β-propiolactone-altered human albumin in the vaccines.

Managing adverse events

Once started, do not delay or stop rabies post-exposure prophylaxis because of local reactions or mild systemic reactions. Simple analgesics can help manage these reactions.

Because rabies is almost always fatal, the recommended vaccination regimens, especially the post-exposure prophylaxis regimen, should be continued even if the person has a significant allergic reaction after a dose of rabies vaccine. Antihistamines can lessen the symptoms of any subsequent reactions.

Carefully consider the person’s risk of developing either lyssavirus infection or rabies before deciding to stop the vaccination regimen.

Adverse events following human rabies immunoglobulin

Human rabies immunoglobulin has an excellent safety profile, and generally no chance of immediate hypersensitivity reactions. Hypersensitivity reactions are more common with some equine rabies immunoglobulins used overseas.

Nature of the disease

Lyssaviruses are single-stranded RNA viruses in the family Rhabdoviridae, genus Lyssavirus. There are 12 known species in the genus Lyssavirus, including classical rabies virus and closely related lyssaviruses such as ABLV (Australian bat lyssavirus) and European bat lyssaviruses.54

Clinical features

Rabies is a zoonotic disease caused by exposure to saliva or neural tissue of an animal infected with rabies virus or other lyssaviruses.

The clinical diseases caused by classical rabies virus and other lyssaviruses are indistinguishable. The term ‘rabies’ refers to disease caused by any of the known lyssavirus species.

Rabies is almost always fatal.

Transmission of rabies and lyssaviruses

Humans can be exposed by:55

- an animal scratch or bite that has broken the skin

- direct contact of the virus with the mucosal surface of a person, such as nose, eye or mouth

- tissue or organ transplantation from donors who died with undiagnosed rabies

It is rare for people to acquire rabies if:

- an animal scratches them

- an animal licks an open wound

- animal saliva contacts intact mucous membranes

Aerosol transmission has never been well documented in the natural environment.56

Transmission of rabies virus to humans through unpasteurised milk may be possible. However, rare reports of transmission by this route have not been confirmed.57

Incubation period

Once a person is infected, the incubation period of rabies is usually 3–8 weeks. This can range from as short as 1 week to, on rare occasions, several years.

The risk of rabies is higher, and the incubation period is shorter:

- after severe and multiple wounds near the central nervous system (such as on the head and neck)

- in richly innervated sites (such as the fingers)

Initial symptoms of rabies

The rabies prodromal phase lasts up to 10 days. During this phase, the person may experience non-specific symptoms such as:40

- anorexia

- cough

- fever

- headache

- myalgia and fatigue

- nausea and vomiting

- sore throat

The person may have abnormal sensations (paraesthesiae) or muscle twitches (fasciculations) at or near the site of the wound. They may also experience anxiety, agitation and apprehension.

Death from rabies

Most people with rabies present with the furious (also called encephalitic) form.41

In the encephalitic phase, objective signs of nervous system involvement include:41

- aerophobia

- hydrophobia

- bizarre behaviour

- disorientation

- hyperactivity

- hypersalivation, hyperthermia and hyperventilation (signs of autonomic instability)

The person’s neurological status deteriorates over a period of up to 12 days. Death occurs either abruptly from cardiac or respiratory arrest, or following coma.

Epidemiology

Rabies epidemiology varies depending on the lyssavirus species and the animal host. Lyssaviruses have been found on all continents except Antarctica.

Australian state or territory health authorities can advise about potential lyssavirus exposures and their management. See Public health management.

International authorities can provide information about the global occurrence of rabies.

Classical rabies virus in terrestrial animals

Rabies that is due to classical rabies virus and occurs in terrestrial mammals is present throughout much of Africa, Asia and the Americas, and parts of Europe. In these regions, the virus is maintained in certain species of mammals, particularly dogs.26

In countries where rabies vaccination of domestic animals is widespread (North America and Europe), wild animals such as raccoons and foxes are important reservoirs. The continual maintenance of rabies in animal populations in these countries is referred to as enzootic rabies.

A country’s status can change at any time. For example, in 2008 on the island of Bali, Indonesia, rabies was reported in dogs, and cases were later reported in humans.58 Before this, Bali had been considered free from rabies, although rabies was known to occur in other areas of Indonesia.59 Public Health England maintains a list of rabies risk from terrestrial animals by country.

Australian bat lyssavirus

In some parts of the world, bats are important reservoirs of classical rabies virus as well as other lyssaviruses. Bat lyssaviruses are found in some areas that are considered to be free from terrestrial rabies, including Australia.

ABLV (Australian bat lyssavirus) was first reported in bats in 1996. Since then, 3 cases of fatal encephalitis caused by ABLV have been reported in Australians, in 1996, 1998 and 2013.60-62 All 3 patients had been either bitten or scratched by bats.

Evidence of ABLV infection has been identified in all 4 species of Australian fruit bats (flying foxes) and in several species of Australian insectivorous bats. It should therefore be assumed that all Australian bats can be infected with ABLV.

The first confirmed cases of ABLV in terrestrial mammals in Australia occurred in 2 horses in Queensland in 2013.63

Bat lyssavirus infections in terrestrial animals are extremely rare in areas where rabies is not enzootic, such as Australia. There is no evidence of transmission from an infected terrestrial animal to humans. However, this is theoretically possible.

Lyssaviruses in bats worldwide

Bats anywhere in the world are a potential source of lyssaviruses and a potential risk for acquiring rabies, depending on how a person is exposed.

ABLV has not been isolated from bats outside Australia.

However, bats in other countries have closely related lyssaviruses. For example, bats in some parts of Europe can have European bat lyssavirus 1 and European bat lyssavirus 2. At least 4 people have died from European bat lyssavirus variants. None of them had a record of prophylactic rabies immunisation.64,65

There are rare reports of bat lyssavirus infections in other animals66-68 (such as ABLV in horses).

Vaccine and immunoglobulin information

2 inactivated rabies cell culture–derived vaccines are available in Australia.

Rabies vaccine is effective when used for pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies.26,47,69 Although data on the effectiveness of rabies vaccine as prophylaxis against other lyssaviruses are limited, the available animal data and clinical experience support its use.32,34,70-74

A 3-dose intramuscular (IM) pre-exposure prophylaxis regimen has superior performance to a 3-dose intradermal (ID) regimen with respect to the magnitude of primary antibody response.75-78 However, studies demonstrate that short-term and long-term anamnestic response following standard ID pre-exposure prophylaxis is similar to that following IM exposure, provided that the ID doses are delivered correctly. A booster dose administered up to 1 year following an accelerated pre-exposure schedule (1, 2 or 3 doses, IM or ID) will also produce an effective anamnestic response by day 7–14.10

The immunogenicity of the 2 rabies vaccines registered and marketed in Australia — Rabipur (purified chick embryo cell vaccine) and Verorab (purified Vero cell rabies vaccine) — have been assessed in individuals who have potentially been exposed to rabies and in healthy volunteers.69,79,80 In the majority of studies, 100% of study participants had geometric mean titres (GMTs) above 0.5 IU/mL by day 14. In all studies that assessed antibody response at day 30, after receiving 4 doses of the rabies vaccine, 100% of participants had GMTs >0.5 IU/mL.28,29,69,81,82

In people who are severely immunocompromised, the immune response to rabies vaccination may be suboptimal.1 People who are mildly or moderately immunocompromised and have been previously primed with rabies vaccine can mount an immune response after only 2 doses of post-exposure prophylaxis. However, people who are more severely immunocompromised may mount a lower immune response.83

Numerous clinical studies of both IM and ID pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis regimens have shown VNAb (virus neutralising antibody) titres >0.5 IU per mL on days 28 and 90, and VNAb levels did not fall below 0.5 IU per mL until day 180. These data demonstrate that people who receive a rabies pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis regimen do not require revaccination if they are exposed again within 3 months.84

2-visit pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) schedules

Studies of HDCV and PCECV rabies vaccines show that a 2 dose PrEP schedule produces an immune response that is comparable to a 3 dose PrEP schedule, particularly in the 7-28 days after vaccination.

Three clinical trials showed that the 2 dose PrEP schedule produced a rabies VNAb seroconversion rate (96.7 – 100%), a measure of whether the immune system has responded to the vaccine, that was comparable to the 3 dose PrEP schedule (100%) in the 7–28 days after vaccination.69,85,86 Similar results were also produced in observational studies at this time point.7,87,88

A clinical trial showed that the 2 dose PrEP schedule produced a rabies VNAb seroconversion rate that was slightly reduced (46%) compared to the 3 dose PrEP schedule (55%) at 180 days after vaccination.69

There is limited and uncertain evidence on the long-term duration of 2 doses of PrEP verses 3 doses of PrEP. Three clinical trials showed that the 2 dose PrEP schedule produced a rabies VNAb seroconversion rate that was reduced (7–60%) compared to the 3 dose PrEP schedule (35–64%) at 365 days or more after vaccination.69,85,86 Similar results were also shown in observational studies.7,88,89 The clinical significance of this difference in seroconversion rates between 2 PrEP doses versus 3 PrEP doses, is unknown.

Studies of PVRV rabies vaccines show that a 2 dose PrEP schedule produces an immune response that is comparable to a 3 dose PrEP schedule, particularly in the 14-28 days after vaccination. These studies compared either 2 doses or 3 doses of Verorab in a PrEP schedule to the same number of doses of HDCV or PCECV rabies vaccines and found Verorab to be non-inferior in terms of immunogenicity and equivalent for safety.45,46,69,87,89

Transporting, storing and handling vaccines

Rabies vaccine

Transport according to National vaccine storage guidelines: Strive for 5.91 Store at +2°C to +8°C. Do not freeze.

All rabies vaccines must be reconstituted. Add the entire contents of the diluent container to the vial and shake until the powder completely dissolves. Use the reconstituted vaccine immediately.

Human rabies immunoglobulin

Transport according to National vaccine storage guidelines: Strive for 5.91 Store at +2°C to +8°C. Do not freeze. Protect from light.

Use immediately after opening the vial.

Public health management

Classical rabies virus and ABLV (Australian bat lyssavirus) infections in humans are notifiable diseases in all states and territories in Australia.

Other lyssavirus cases that do not meet the case definition for ABLV or rabies virus infection are also notifiable in all states and territories in Australia.

The Communicable Diseases Network Australia national guidelines for rabies virus and other lyssavirus exposures and infections have details about the management of rabies and other lyssavirus infections, including ABLV.

State and territory public health authorities can provide further advice about the public health management of rabies and other lyssavirus infections.

Both human rabies immunoglobulin and rabies vaccine are available for post-exposure prophylaxis from state and territory public health authorities.

Variations from product information

Use in pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis

The product information for the 2 vaccines available in Australia states that they can be used for both pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis for ABLV (Australian bat lyssavirus) exposures.

ATAGI (the Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation) recommends that, where indicated, any of the available rabies vaccines can be used as pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis for ABLV exposures, as well as exposure to classical rabies virus and other lyssaviruses — see Recommendations.

Purified chick embryo cell vaccine for pre-exposure prophylaxis

The product information for purified chick embryo cell vaccine states that it is for intramuscular injection only.

ATAGI recommends that the intradermal route is an acceptable alternative to the intramuscular route for pre-exposure prophylaxis.

The product information for purified chick embryo cell vaccine recommends that, for people who are considered to be at ongoing risk of exposure to rabies (eg veterinarians and their assistants, wildlife workers, hunters), a serological test should usually be performed at least every 2 years, with shorter intervals if appropriate to the perceived degree of risk.

ATAGI recommends boosters every 3 years for people at ongoing occupational risk. See People with ongoing occupational exposure to lyssaviruses are recommended to receive booster doses of rabies vaccine in Recommendations.

Purified chick embryo cell vaccine for post-exposure prophylaxis

The product information for purified chick embryo cell vaccine recommends a routine 5th dose at 28 days for post-exposure prophylaxis.

ATAGI recommends that immunocompetent people can receive a 4-dose schedule with either cell culture–derived vaccine for post-exposure prophylaxis.

ATAGI recommends that people who are immunocompromised can receive a 5th dose at day 28.

ATAGI recommends that people who are immunocompromised and have a rabies VNAb titre <0.5 IU per mL after the 5th dose of post-exposure prophylaxis can receive further doses.

References

- Tantawichien T, Jaijaroensup W, Khawplod P, Sitprija V. Failure of multiple-site intradermal postexposure rabies vaccination in patients with human immunodeficiency virus with low CD4+ T lymphocyte counts. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001;33:E122–4.

- Kopel E, Oren G, Sidi Y, David D. Inadequate antibody response to rabies vaccine in immunocompromised patient. Emerging Infectious Diseases 2012;18:1493-5.

- Gongal G, Sampath G. Introduction of intradermal rabies vaccination - A paradigm shift in improving post-exposure prophylaxis in Asia. Vaccine 2019;37 Suppl 1:A94-a8.

- Endy TP, Keiser PB, Cibula D, et al. Effect of antimalarial drugs on the immune response to intramuscular rabies vaccination using a postexposure prophylaxis regimen. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020;221:927-33.

- Garcia Garrido HM, van Put B, Terryn S, et al. Immunogenicity and 1-year boostability of a three-dose intramuscular rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis schedule in adults receiving immunosuppressive monotherapy: a prospective single-centre clinical trial. Journal of Travel Medicine 2023;30.

- Furuya-Kanamori L, Ramsey L, Manson M, Gilbert B, Lau CL. Intradermal rabies pre-exposure vaccination schedules in older travellers: comparison of immunogenicity post-primary course and post-booster. Journal of Travel Medicine 2020;27.

- Mills DJ, Lau CL, Fearnley EJ, Weinstein P. The immunogenicity of a modified intradermal pre-exposure rabies vaccination schedule--a case series of 420 travelers. Journal of Travel Medicine 2011;18:327-32.

- Xu C, Lau CL, Clark J, et al. Immunogenicity after pre- and post-exposure rabies vaccination: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis. Vaccine 2021;39:1044-50.

- Guo Y, Mills DJ, Lau CL, Mills C, Furuya-Kanamori L. Immune response after rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis and a booster dose in Australian bat carers. Zoonoses Public Health 2023.

- Langedijk AC, De Pijper CA, Spijker R, et al. Rabies antibody response after booster immunization: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2018;67:1932-47.

- De Pijper CA, Langedijk AC, Terryn S, et al. Long-term memory response after a single intramuscular rabies booster vaccination 10-24 years after primary immunization. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022;226:1052-6.

- Giovanetti F. Immunisation of the travelling child. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 2007;5:349-64.

- Gunther A, Burchard GD, Schoenfeld C. Rabies vaccination and traffic accidents [letter]. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 2008;6:326-7.

- Neilson AA, Mayer CA. Rabies: prevention in travellers. Australian Family Physician 2010;39:641-5.

- Gautret P, Schwartz E, Shaw M, et al. Animal-associated injuries and related diseases among returned travellers: a review of the GeoSentinel Surveillance Network. Vaccine 2007;25:2656-63.

- Meslin FX. Rabies as a traveler's risk, especially in high-endemicity areas. Journal of Travel Medicine 2005;12 Suppl 1:S30-40.

- Mudur G. Foreign visitors to India are unaware of rabies risk. BMJ 2005;331:255.

- Piyaphanee W, Shantavasinkul P, Phumratanaprapin W, et al. Rabies exposure risk among foreign backpackers in Southeast Asia. American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2010;82:1168-71.

- Mills DJ, Lau CL, Weinstein P. Animal bites and rabies exposure in Australian travellers. Medical Journal of Australia 2011;195:673-5.

- Gherardin AW, Scrimgeour DJ, Lau SC, Phillips MA, Kass RB. Early rabies antibody response to intramuscular booster in previously intradermally immunized travelers using human diploid cell rabies vaccine. Journal of Travel Medicine 2001;8:122-6.

- Mansfield KL, Andrews N, Goharriz H, et al. Rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis elicits long-lasting immunity in humans. Vaccine 2016;34:5959-67.

- Lim PL, Barkham TM. Serologic response to rabies pre-exposure vaccination in persons with potential occupational exposure in Singapore. International Journal of Infectious Diseases 2010;14:e511-3.

- Morris J, Crowcroft NS, Fooks AR, Brookes SM, Andrews N. Rabies antibody levels in bat handlers in the United Kingdom: immune response before and after purified chick embryo cell rabies booster vaccination. Hum Vaccin 2007;3:165-70.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Manning SE, Rupprecht CE, et al. Human rabies prevention – United States, 2008: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. MMWR. Recommendations and Reports 2008;57(RR-3):1-28.

- McElhinney LM, Marston DA, Brookes SM, Fooks AR. Effects of carcase decomposition on rabies virus infectivity and detection. Journal of Virological Methods 2014;207:110-3.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper – April 2018. Weekly Epidemiological Record 2018;93:201-19.

- Jones RL, Froeschle JE, Atmar RL, et al. Immunogenicity, safety and lot consistency in adults of a chromatographically purified Vero-cell rabies vaccine: a randomized, double-blind trial with human diploid cell rabies vaccine. Vaccine 2001;19:4635-43.

- Wang C, Zhang X, Song Q, Tang K. Promising rabies vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis in developing countries, a purified Vero cell vaccine produced in China. Clinical and Vaccine Immunology 2010;17:688-90.

- Wang XJ, Lang J, Tao XR, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of purified Vero-cell rabies vaccine in severely rabies-exposed patients in China. Southeast Asian Journal of Tropical Medicine and Public Health 2000;31:287-94.

- Wilde H. Failures of post-exposure rabies prophylaxis. Vaccine 2007;25:7605-9.

- Bose A, Munshi R, Tripathy RM, et al. A randomized non-inferiority clinical study to assess post-exposure prophylaxis by a new purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (Rabivax-S) administered by intramuscular and intradermal routes. Vaccine 2016;34:4820-6.

- Brookes SM, Parsons G, Johnson N, McElhinney LM, Fooks AR. Rabies human diploid cell vaccine elicits cross-neutralising and cross-protecting immune responses against European and Australian bat lyssaviruses. Vaccine 2005;23:4101-9.

- Lang J, Simanjuntak GH, Soerjosembodo S, Koesharyono C. Suppressant effect of human or equine rabies immunoglobulins on the immunogenicity of post-exposure rabies vaccination under the 2 1 1 regimen: a field trial in Indonesia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization 1998;76:491-5.

- Nel LH. Vaccines for lyssaviruses other than rabies. Expert Review of Vaccines 2005;4:533-40.

- Sampath G, Madhusudana SN, Sudarshan MK, et al. Immunogenicity and safety study of Indirab: a Vero cell based chromatographically purified human rabies vaccine. Vaccine 2010;28:4086-90.

- Vodopija I, Sureau P, Smerdel S, et al. Interaction of rabies vaccine with human rabies immunoglobulin and reliability of a 2 1 1 schedule application for postexposure treatment. Vaccine 1988;6:283-6.

- Chutivongse S, Wilde H, Benjavongkulchai M, Chomchey P, Punthawong S. Postexposure rabies vaccination during pregnancy: effect on 202 women and their infants. Clinical Infectious Diseases 1995;20:818-20.

- Sudarshan MK, Giri MS, Mahendra BJ, et al. Assessing the safety of post-exposure rabies immunization in pregnancy. Human Vaccines 2007;3:87-9.

- Suwansrinon K, Jaijaroensup W, Wilde H, Sitprija V. Is injecting a finger with rabies immunoglobulin dangerous? American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2006;75:363-4.

- Nel LH, Markotter W. Lyssaviruses. Critical Reviews in Microbiology 2007;33:301-24.

- Jackson AC. Update on rabies. Research and Reports in Tropical Medicine 2011;2:31-43.

- Rupprecht CE, Hanlon CA, Hemachudha T. Rabies re-examined. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2002;2:327-43.

- Briggs DJ, Dreesen DW, Nicolay U, et al. Purified chick embryo cell culture rabies vaccine: interchangeability with human diploid cell culture rabies vaccine and comparison of one versus two-dose post-exposure booster regimen for previously immunized persons. Vaccine 2000;19:1055-60.

- Rupprecht CE, Nagarajan T, Ertl H. Rabies vaccines. In: Plotkin SA, Orenstein WA, Offit PA, Edwards KM, eds. Plotkin's vaccines. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2018.

- Shanbag P, Shah N, Kulkarni M, et al. Protecting Indian schoolchildren against rabies: pre-exposure vaccination with purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV) or purified verocell rabies vaccine (PVRV). Hum Vaccin 2008;4:365-9.

- Ajjan N, Pilet C. Comparative study of the safety and protective value, in pre-exposure use, of rabies vaccine cultivated on human diploid cells (HDCV) and of the new vaccine grown on Vero cells. Vaccine 1989;7:125-8.

- Dobardzic A, Izurieta H, Woo EJ, et al. Safety review of the purified chick embryo cell rabies vaccine: data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 1997–2005. Vaccine 2007;25:4244-51.

- Madhusudana SN, Sanjay TV, Mahendra BJ, et al. Comparison of safety and immunogenicity of purified chick embryo cell rabies vaccine (PCEV) and purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV) using the Thai Red Cross intradermal regimen at a dose of 0.1 mL. Human Vaccines 2006;2:200-4.

- Mattner F, Bitz F, Goedecke M, et al. Adverse effects of rabies pre- and postexposure prophylaxis in 290 health-care-workers exposed to a rabies infected organ donor or transplant recipients. Infection 2007;35:219-24.

- Mattner F, Henke-Gendo C, Martens A, et al. Risk of rabies infection and adverse effects of postexposure prophylaxis in healthcare workers and other patient contacts exposed to a rabies virus-infected lung transplant recipient. Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology 2007;28:513-8.