Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

Information about respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease, vaccines and recommendations for vaccination from the Australian Immunisation Handbook.

Recently added

This page was added on 27 June 2024.

Updates made

This page was updated on 19 January 2026. View history of updates

This chapter is currently undergoing consultation and seeking National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) approval.

Abrysvo is funded under the National Immunisation Program (NIP) for eligible pregnant women.

States and territories have funding for RSV specific monoclonal antibodies for certain groups of infants and young children. See state and territory guidance for details of each program.

Vaccination for older adults against this disease is not funded under the National Immunisation Program, nor by states and territories.

Overview

What

RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) is a virus that causes upper and lower respiratory tract infection. RSV infection can cause severe disease, particularly in very young and older people.

Who

RSV vaccination is recommended for:

- pregnant women to protect their newborn infant

- all people aged ≥75 years and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people aged ≥60 years

- people with medical risk factors for severe RSV disease aged ≥60 years.

RSV monoclonal antibodies are recommended for:

- young infants whose mothers did not receive RSV vaccine in pregnancy, or who were not vaccinated at least 2 weeks before giving birth

- young infants who are at increased risk of severe RSV disease, regardless of their mother’s vaccination status

- children aged <24 months who have medical risk factors for severe RSV disease in their 2nd or subsequent RSV season.

Non-Indigenous adults aged 60–74 years who do not have a medical risk factor for severe RSV disease may also consider vaccination. There are benefits of vaccination in this age group, but the benefits may be less than for those aged ≥75 years, because of a comparatively lower risk of severe RSV disease.

Adults aged 50–59 years who have a medical risk factor for severe RSV disease may also consider vaccination.

Risk factors for severe RSV disease differ between infants (see Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children) and adults (see Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in adults).

How

A single dose of RSV vaccine is recommended to protect older people. RSV vaccine may be given at any time of the year, but, where possible, should be offered before the start of the RSV season. The 2 RSV vaccines registered for use in adults aged ≥60 years are Abrysvo and Arexvy. There is no brand preference for this age group. The need for further doses has not yet been established.

A single dose of Abrysvo is recommended for use in pregnant women to protect their infants. Administration is recommended from 28 weeks gestation. Infants are unlikely to be adequately protected if they are born less than 2 weeks after their mother received the vaccine, so administration by 36 weeks is encouraged.1 Advice on revaccination in subsequent pregnancies will be provided when data are available.

A single dose of nirsevimab – a long-acting RSV-specific monoclonal antibody – is recommended before their 1st RSV season in young infants whose:

- mothers who were not vaccinated at least 2 weeks before giving birth

- protection from maternal vaccination may be reduced because of maternal or infant conditions

Additionally, children with medical risk factors who may need additional protection before their 1st or 2nd RSV season are recommended to receive monoclonal antibody. A short-acting monoclonal antibody (palivizumab), which is given monthly for 5 months, is recommended only if nirsevimab is not available, from shortly before the start of the RSV season for infants who have medical risk factors for severe RSV.

Why

RSV infects most children by 2 years of age. RSV infection is associated with substantial disease burden (in both inpatient and outpatient settings) and is a leading cause of lower respiratory tract disease hospitalisation in infants aged <12 months.2-6 Most infants hospitalised with RSV disease are otherwise healthy.4 However, those with medical risk factors have an increased risk of severe disease.

RSV is also an important cause of respiratory disease and hospitalisation in older people, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults, and people with conditions that increase their risk of severe RSV disease.

Recommendations

Infants and children

-

A single dose of the RSV vaccine Abrysvo is recommended for all pregnant women from 28 weeks gestation, as the first opportunity to protect their infant. See Pregnant women are recommended to receive an RSV vaccine during pregnancy to protect the infant. Do not give RSV vaccine Abrysvo to infants and young children.

Nirsevimab is a long-acting RSV-specific monoclonal antibody that is recommended for infants who were born:

- to women who did not receive RSV vaccine during pregnancy

- <2 weeks after the mother received RSV vaccine during pregnancy

Nirsevimab is also recommended for the following infants after assessment by their treating doctor to confirm potential clinical benefit:

- infants with risk conditions for severe RSV disease, regardless of maternal vaccination (see Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children)

- infants born to mothers with severe immunosuppression, where the immune response to maternally administered RSV vaccine was impaired (see People who are severely immunocompromised)

- infants who have lost effective passive immunisation:

- those whose mothers have received RSV vaccine in pregnancy but who have subsequently undergone a treatment after birth, such as exchange transfusion, cardiopulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, that may lead to loss of maternal antibodies, OR

- those who have already received nirsevimab but have subsequently undergone one of the procedures above (noting this would be a repeat dose of nirsevimab)

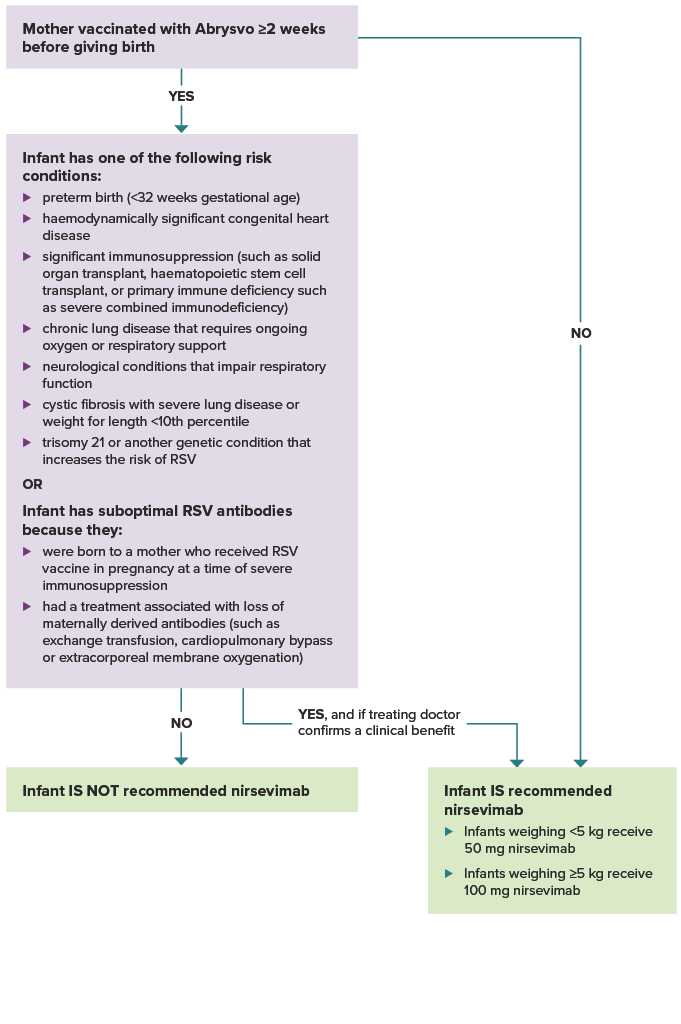

See Figure. Flowchart to guide which infants should receive nirsevimab in their 1st RSV season.

Nirsevimab is not recommended for infants during the first 6 months of life if:

- the infant’s mother received RSV vaccine at an appropriate time during pregnancy, AND

- the infant does not have a risk condition for severe RSV disease

Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young childrenRisk category Details or specific conditions Preterm birth - Born <32 weeks gestational age

Cardiac disease - Haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease

Significant immunosuppression (individual conditions listed and those that are similar based on clinical judgement) Examples include:

- Malignancy

- Solid organ transplant

- Haematopoietic stem cell transplant

- Inborn errors of immunity associated with T cell or combined immunodeficiency, such as severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID)

Chronic respiratory disease - Chronic lung disease requiring ongoing oxygen or respiratory support

- Cystic fibrosis with severe lung disease or weight for length <10th percentile

Neurological conditions that impair respiratory function (individual conditions listed and those that are similar based on clinical judgement) Examples include:

- Congenital, hereditary, or degenerative central nervous system disorders

- Cerebral Palsy

- Brain or spinal cord conditions affecting respiratory control / function

- Neuromuscular disorders

- Conditions with impaired swallowing/coughing or with aspiration risk

Chromosomal abnormality - Trisomy 21 or another genetic condition that increases the risk of severe RSV disease

Figure. Flowchart to guide which infants should receive nirsevimab in their 1st RSV season

Show description of image

Was the mother vaccinated with Abrysvo at least 2 weeks before giving birth? If yes, and the infant does not have one of the risk conditions or conditions for suboptimal antibodies listed below, the infant is not recommended nirsevimab.

If the mother was not vaccinated at least 2 weeks before delivery, the infant is recommended nirsevimab. Infants weighing less than 5 kg receive 50 mg nirsevimab. Infants weighing 5 kg or more receive 100 mg nirsevimab.

If the mother was vaccinated at least 2 weeks before delivery, does the infant have one of the following risk conditions: preterm birth (<32 weeks gestational age), haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. significant immunosuppression (such as from malignancy, solid organ transplant, haematopoietic stem cell transplant, or primary immune deficiency such as severe combined immunodeficiency), chronic lung disease that requires ongoing oxygen or respiratory support, neurological conditions that impair respiratory function, cystic fibrosis with severe lung disease or weight for length <10th percentile, trisomy 21 or another genetic condition that increases the risk of RSV? Or, does the infant have suboptimal RSV antibodies because they were born to a mother who received RSV vaccine in pregnancy at a time of severe immunosuppression, or they had a treatment associated with loss of maternally derived antibodies (such as exchange transfusion, cardiopulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation)? If the infant does not have a risk condition or suboptimal RSV antibodies, they are not recommended nirsevimab. If the infant does have a risk condition or suboptimal RSV antibodies, they are recommended nirsevimab if their treating doctor confirms a clinical benefit.

Other general considerations on the use of RSV monoclonal antibody

Other general considerations on the use of RSV monoclonal antibody

- Infants <3 months of age in their 1st RSV season have a greater risk of severe disease than older children in all categories.

- Infants with multiple risk factors for severe RSV disease, such as preterm birth and a medical risk condition, are likely to have an even higher risk of severe outcomes.

- The risk of hospitalisation from RSV for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander infants is around 2 times that of non-Indigenous infants of the same age.7,8

- Infants who live in regions where advanced care for severe RSV is not readily accessible may have greater benefit.

- Palivizumab (short acting RSV mAB) may be available as an alternative RSV monoclonal antibody for eligible infants. Palivizumab is recommended for infants who have a risk condition (i.e. not for infants born to an unvaccinated mother). See Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children. Palivizumab is given as up to 5 monthly injections from shortly before the start of the RSV season.

View recommendation detailsTiming of RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies in infants

Timing of RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies in infants

The timing of administration of monoclonal antibody should ensure that the duration and level of protection are maximised over the peak months of a child’s 1st RSV season. This is typically April to September in temperate regions of Australia, but this may vary for different regions. Local advice should be sought. Infants who have previously had an RSV infection who are recommended to receive RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies can receive it once recovered.

Nirsevimab offers protection for at least 5 months, with early immunogenicity evidence suggesting some protection may remain for 6-12 months.9 Protective benefits can be maximised if it is administered:

- shortly after birth for infants born just before or during the RSV season. For infants born after the RSV season, consider the likelihood of out-of-season RSV infection and risk of severe disease (see Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children), and consider delaying nirsevimab until just before the next RSV season, if appropriate

- shortly before the start of their 1st RSV season in older infants that remain at high risk.

Infants and young children who are at risk of severe RSV disease and who have previously had an RSV infection and are recommended to receive RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies can receive it once recovered.

Nirsevimab is funded through state and territory programs for some infants and young children. See state and territory guidance for details of each program.

-

Young children aged 8 to <24 months who have certain risk conditions for severe RSV disease are recommended to receive RSV-specific monoclonal antibody before their 2nd or subsequent RSV season. See Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children.

This is regardless of whether these at-risk children received a dose of RSV-specific monoclonal antibody in their first RSV season or were born to a mother who received RSV vaccine during pregnancy.

If a child has already received nirsevimab and has since undergone a treatment, such as cardiopulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, that may lead to loss of RSV-specific antibodies, a repeat dose is recommended.

Nirsevimab is preferred over palivizumab.

The dose of nirsevimab for an older infant or child is up to 4 times higher than the dose for a newborn. See Vaccines, dosage and administration.

View recommendation detailsTiming of RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies in at-risk children entering their 2nd or subsequent RSV season

Timing of RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies in at-risk children entering their 2nd or subsequent RSV season

Nirsevimab offers protection for at least 5 months. Protective benefits can be maximised if it is administered shortly before the start of the RSV season. This is typically April to September in temperate regions of Australia, although this may vary for different regions. Local advice should be sought.

Infants and young children who are at risk of severe RSV disease and who have previously had an RSV infection and are recommended to receive RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies can receive it once recovered.

A minimum interval of 6 months is recommended between each season’s dose of nirsevimab. However, a longer interval may be appropriate. The timing of the second dose should consider the timing of the RSV season, the age of the infant and whether they have risk factors for severe RSV disease.

Nirsevimab is funded through state and territory programs for some infants and young children. See state and territory guidance for details of each program.

Adults

-

A single dose of RSV vaccine is recommended for all adults aged ≥75 years. RSV hospitalisation rates increase with age, and people aged ≥75 years are likely to have the greatest benefit from vaccination.

RSV vaccine may be given at any time of the year but, where possible, should be offered before the start of the RSV season. Adults recommended to receive an RSV vaccine, who have previously had an RSV infection, can receive it once they are recovered.

Either Abrysvo or Arexvy may be used, with no brand preference.

Protection lasts for at least 2 years, and the need for further doses has not been established.

View recommendation details -

Adults aged 60–74 years who do not have a risk factor for severe RSV disease can consider a single dose of RSV vaccine. People in this age group have a lower risk of severe RSV disease than people aged ≥75 years, so the benefit may be less than in people aged ≥75 years.

RSV vaccine may be given at any time of the year but, where possible, should be offered before the start of the RSV season. Adults recommended to receive an RSV vaccine, who have previously had an RSV infection, can receive it once they are recovered.

Either Abrysvo or Arexvy may be used, with no brand preference.

Protection lasts for at least 2 years, and the need for further doses has not been established.

View recommendation details

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people

-

A single dose of RSV vaccine is recommended for all Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults aged ≥60 years. The burden of RSV disease is significantly higher in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people than in non-Indigenous adults. For example, the RSV-related hospitalisation rate at 60 years of age in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander adults is comparable to the rate in non-Indigenous adults at 75 years of age.

RSV vaccine may be given at any time of the year but, where possible, should be offered before the start of the RSV season. Adults recommended to receive an RSV vaccine, who have previously had an RSV infection, can receive it once they are recovered.

Either Abrysvo or Arexvy may be used, with no brand preference.

Protection lasts for at least 2 years, and the need for further doses has not been established.

View recommendation details

People with medical conditions that increase their risk of severe RSV disease

-

Adults aged 50–59 years who have a risk factor for severe RSV disease can consider a single dose of Arexvy. See Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in adults.

Arexvy is the only vaccine registered for use in people aged 50-59 years with medical conditions that increase their risk of severe disease.

RSV vaccine may be given at any time of the year but, where possible, should be offered before the start of the RSV season. Adults recommended to receive an RSV vaccine, who have previously had an RSV infection, can receive it once they are recovered.

Protection lasts for at least 2 years, and the need for further doses has not been established.

View recommendation detailsTable. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in adultsAdults aged ≥50 years with the medical conditions listed below are at increased risk of severe RSV disease. These examples are not exhaustive, and providers may include people with conditions similar to those listed below based on clinical judgement.

Risk category Example medical condition Cardiac disease - Congenital heart disease

- Congestive heart failure

- Coronary artery disease

Chronic respiratory conditions - Suppurative lung disease

- Bronchiectasis

- Cystic fibrosis

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- Chronic emphysema

- Severe asthma (requiring frequent medical consultations or the use of multiple medications)

Immunocompromising conditions - HIV infection

- Malignancy

- Immunocompromise due to disease or treatment

- Asplenia or splenic dysfunction

- Solid organ transplant

- Haematopoietic stem cell transplant

- CAR T-cell therapy

Chronic metabolic disorders - Type 1 or 2 diabetes

- Amino acid disorders

- Carbohydrate disorders

- Cholesterol biosynthesis disorders

- Fatty acid oxidation defects

- Lactic acidosis

- Mitochondrial disorders

- Organic acid disorders

- Urea cycle disorders

- Vitamin/cofactor disorders

- Porphyrias

Chronic kidney disease - Chronic renal impairment – eGFR <30 mL/min (stage 4 or 5)

Chronic neurological conditions - Hereditary and degenerative central nervous system diseases

- Seizure disorders

- Spinal cord injuries

- Neuromuscular disorders

- Other conditions that increase the risk of severe outcomes from respiratory infection

Chronic liver disease - Conditions with progressive deterioration of liver function for more than 6 months including cirrhosis and other advanced liver diseases

Obesity - Body mass index ≥30 kg per m2

-

View recommendation details

A single dose of RSV vaccine is recommended for adults aged ≥60 years with risk factors for severe RSV disease. See Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in adults.

RSV vaccine may be given at any time of the year but, where possible, should be offered before the start of the RSV season. Adults recommended to receive an RSV vaccine, who have previously had an RSV infection, can receive it once they are recovered.

Either Abrysvo or Arexvy may be used, with no brand preference.

Protection lasts for at least 2 years, and the need for further doses has not been established.

Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding

-

A single dose of Abrysvo is recommended for all pregnant women (including those aged <18 years) from 28 weeks gestation to protect their infant.

Abrysvo is the only RSV vaccine approved for use in pregnant women. Arexvy should not be given to pregnant women. See precautions.

See Table. Vaccines that are routinely recommended in pregnancy: inactivated vaccines in Vaccination for women who are planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding for more details. See Vaccine recommendations for pregnant women – a guide for health professionals.

RSV infection in infants often causes lower respiratory tract disease, such as bronchiolitis. It is most likely to be severe during the first 6 months of life, frequently requiring hospitalisation. Maternal immunisation reduces the risk of severe RSV disease in infants <6 months of age by around 70% (see Vaccine information). This is the result of passive protection by transplacental transfer of RSV-specific antibodies from the mother to the fetus during pregnancy.

Maternal RSV vaccine is administered mainly to protect newborn infants. Vaccination may also protect pregnant women against RSV disease, but this is usually mild in women of child-bearing age and clinical trials did not study protection to the mother from vaccination.

Advice on potential repeat vaccination during subsequent pregnancies will be provided in the future as more data become available. The need for vaccination during each pregnancy is anticipated based on immunologic principles and experience with other vaccines recommended in pregnancy.

Women who are breastfeeding but not pregnant are not recommended to receive an RSV vaccine. There are no theoretical safety concerns, but there is also limited evidence that vaccination would protect their infant through breastfeeding alone.

View recommendation detailsTiming of vaccination during pregnancy

Timing of vaccination during pregnancy

The recommended time for RSV vaccination during pregnancy is from 28 weeks gestation. Although Abrysvo is registered from 24 to 36 weeks gestation, administration from 24 to <28 weeks of gestation is not routinely recommended until there are more safety data for women vaccinated at this gestation and their newborn infants.

If a pregnant woman is not vaccinated by 36 weeks gestation, they should receive the vaccine as soon as possible after 36 weeks gestation. An immune response to the vaccine develops within the weeks after vaccination and transplacental antibody transfer to their infant increases progressively from the time of vaccination. However, infants are not expected to be adequately protected unless they are born at least 2 weeks after the mother received the vaccine.1

If birth occurs <2 weeks after the mother received the RSV vaccine, their infant is recommended to receive nirsevimab (a long-acting RSV-specific monoclonal antibody) to provide additional protection. See Neonates and infants aged <8 months whose mothers were not vaccinated at least 2 weeks before giving birth, or who are at increased risk of severe disease, are recommended to receive passive immunisation with a long-acting RSV-specific monoclonal antibody.

If a pregnant woman inadvertently receives RSV vaccine earlier than 28 weeks gestation, a repeat dose during the same pregnancy is not recommended.

The recommended timing of vaccination during pregnancy considers that:

- further safety data on vaccination at an earlier gestational age than 28 weeks will be reviewed as these data become available (see Precautions – women who are pregnant or breastfeeding)

- RSV is a seasonal disease in most parts of Australia, but severe disease can occur outside of peak seasons as RSV circulation continues year-round. Seasonality differs by jurisdiction in Australia, particularly in the tropical regions

- RSV vaccines can be given at the same time as, or separate to, dTpa, influenza and COVID-19 vaccines (see Co-administration with other vaccines) or Rh(D) immunoglobulin (Anti-D).

Abrysvo can be given at any time of the year, regardless of when a pregnant woman is expected to give birth. Pregnant women recommended to receive the vaccine, who have previously had an RSV infection, can receive it once they are recovered.

Abrysvo is funded through the NIP for all pregnant women (including those <18 years of age) from 28 weeks gestation. For details see the National Immunisation Program schedule.

Vaccines, dosage and administration

RSV vaccines available in Australia

The RSV vaccines Abrysvo and Arexvy are different formulations and are registered for use in a specific age or population group.

Only Abrysvo is to be used in pregnant women.

Arexvy is indicated for use in adults aged 50-59 years with medical conditions that increase their risk of severe RSV disease and all older adults aged ≥60 years. Arexvy should not be administered to pregnant women.

Neither RSV vaccine should be given to infants or children, and there are no vaccines currently licensed in this age group. The RSV monoclonal antibodies nirsevimab and palivizumab are available to provide passive immunisation in infants and children aged <2 years. They should not be used in children ≥2 years of age or adults.

The Therapeutic Goods Administration website provides product information for each RSV vaccine.

See also Vaccine information and Variations from product information for more details.

RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies available in Australia

Two monoclonal antibodies are currently available in Australia, Beyfortus (nirsevimab) and Synagis (palivizumab).

Nirsevimab is preferred over palivizumab because it is long acting (it requires only a single dose to cover an RSV season) and is registered for use from birth in all infants.

If nirsevimab is not available, palivizumab may be considered in infants with risk conditions for severe RSV disease. See Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children.

Adults aged ≥60 years and pregnant women for protection of their infant

-

Sponsor:Pfizer AustraliaAdministration route:Intramuscular injection

Registered for use in:

- Pregnant women between 24–36 weeks of gestation

- Individuals ≥60 years

Recombinant Respiratory Syncytial Virus pre-fusion F protein vaccine (RSVPreF)

Powder and diluent for solution for injection

Each 0.5ml reconstituted dose contains:

- RSV subgroup A stabilised prefusion F protein 60 µg

- RSV subgroup B stabilised prefusion F protein 60 µg

- tromethamine

- tromethamine hydrochloride

- sucrose

- mannitol

- polysorbate 80

- sodium chloride

Also contains traces of

- hydrochloric acid

For Product Information and Consumer Medicine Information about Abrysvo visit the Therapeutic Goods Administration website.

View vaccine details

Adults aged ≥60 years and adults 50–59 years who are at increased risk for RSV disease

-

Sponsor:GlaxoSmithKline AustraliaAdministration route:Intramuscular injection

Registered for use in adults aged ≥60 years and adults 50–59 years who are at increased risk for RSV disease

Recombinant Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) pre-fusion F protein (RSVPreF3) (AS01E adjuvanted vaccine)

Powder and suspension for injection

Each 0.5mL reconstituted dose (powder) contains:

- 120µg of RSVPreF3 antigen

- trehalose dihydrate

- polysorbate 80

- monobasic potassium phosphate

- dibasic potassium phosphate

These are adjuvanted with AS01E adjuvant system (suspension). The adjuvant includes:

- 25µg Quillaja saponaria saponin (QS-21)

- 25µg 3-O-desacyl-4’-monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL)

- dioleoylphosphatidylcholine

- cholesterol

- sodium chloride

- dibasic sodium phosphate

- monobasic potassium phosphate

For Product Information and Consumer Medicine Information about Arexvy vaccine visit the Therapeutic Goods Administration website.

View vaccine details

RSV-specific monoclonal antibodies - Infants and children aged <24 months

-

Sponsor:Sanofi-Aventis AustraliaAdministration route:Intramuscular injection

Monoclonal antibody for the prevention of Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) lower respiratory tract infection in:

- Neonates and infants born during or entering their first RSV season

- Children up to 24 months of age who remain vulnerable to severe RSV disease throughout their second RSV season

Siliconised Luer lock Type 1 glass prefilled syringe with a Fluro Tec-coated plunger stopper

Beyfortus 50mg solution for injection in prefilled syringe with a purple plunger rod: Each prefilled syringe contains 50mg of nirsevimab in 0.5mL (100mg/mL)

Beyfortus 100mg solution for injection in prefilled syringe with a light blue plunger rod: Each pre-filled syringe contains 100mg of nirsevimab in 1mL (100mg/mL)

Also contains:

- histidine

- histidine hydrochloride

- monohydrate

- arginine hydrochloride

- sucrose

- polysorbate 80

- water

For Product Information and Consumer Medicine Information about Beyfortus (Nirsevimab) visit the Therapeutic Goods Administration website.

View vaccine details -

Sponsor:AstraZenecaAdministration route:Intramuscular injection

Monoclonal antibody for the prevention of serious lower respiratory tract disease caused by Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) in children at high risk of RSV disease. Safety and efficacy were established in children with bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), infants with a history of prematurity (gestational age less than or equal to 35 weeks at birth) and children with haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease (CHD).

Palivizumab 50 mg/0.5 mL single-use vial: clear, colourless Type 1 glass vial with stopper and flip-off seal containing 0.5 mL palivizumab solution for injection with a concentration of 50mg/mL

Palivizumab 100 mg/1 mL single-use vial: clear, colourless Type 1 glass vial with stopper and flip-off seal containing 1 mL palivizumab solution for injection with a concentration of 100mg/mL

Also contains:

- 25mM histidine

- 1.6 mM glycine

For Product Information and Consumer Medicine Information about Synagis (palivizumab) visit the Therapeutic Goods Administration website.

View vaccine details

Dose and route

Abrysvo and Arexvy

The dose of Abrysvo and Arexvy is 0.5 mL, given by intramuscular injection.

Nirsevimab

The dose of nirsevimab for infants weighing <5 kg, born during or entering their 1st RSV season, is 50 mg (0.5 mL), given by intramuscular injection.

The dose of nirsevimab for infants weighing ≥5 kg, born during or entering their 1st RSV season, is 100 mg (1 mL), given by intramuscular injection.

The dose of nirsevimab for older children entering their 2nd or subsequent RSV season is 200 mg, given as 2 intramuscular injections (2 × 1 mL of the 100 mg/mL formulation) at 2 different sites (preferably separate limbs, or else separated by 2.5 cm) during the same visit.

For children undergoing cardiopulmonary bypass, an additional dose of nirsevimab should be given as soon as the child is stable after surgery.

If the surgery is ≤90 days after receiving nirsevimab:

- The additional dose of nirsevimab for infants born during or entering their first RSV season is based on body weight at the time of the additional dose (see above).

- The additional dose of nirsevimab for older children entering their 2nd or subsequent RSV season is 200 mg (see above).

If the surgery is >90 days after receiving nirsevimab:

- The additional dose of nirsevimab for infants born during or entering their first RSV season is 50mg, regardless of body weight.

- The additional dose of nirsevimab for infants born during or entering their 2nd or subsequent RSV season is 100mg, regardless of body weight.

For children aged ≥12 months, nirsevimab can be given in the deltoid muscle, as for vaccines.

Palivizumab

The dose of palivizumab is 15 mg/kg, each month, given by intramuscular injection up to 5 times during the RSV season. Consult detailed protocols from state and territory health departments or local institution guidelines for more details about using palivizumab.10,11

Vaccine administration errors

For information on vaccine errors see Table. Clinical Guidance on RSV Immunisation Product Administration Errors.

Co-administration with other vaccines

Older adults

Older adults can receive RSV vaccines at the same time as other vaccines, such as COVID-19, influenza, zoster and pneumococcal vaccines. However, co-administration studies on RSV and influenza vaccines have shown slightly lower immune responses to certain strains contained in the RSV vaccine and influenza vaccines compared with when these vaccines are administered separately.12,13 The clinical significance of these decreased immune responses is uncertain.

The likelihood of local and systemic adverse events may also increase with co-administration.12,14 When RSV vaccine was given at the same time as adjuvanted quadrivalent influenza vaccine in clinical trials:13,15

- local adverse events were seen in up to 53% of the co-administered group, compared with 40% when RSV vaccine was given alone

- systemic adverse events were seen in up to 45% of the co-administered group, compared with 34% when RSV vaccine was given alone

The benefits of giving the vaccines at the same time so that people can receive them all during the same visit may outweigh such concerns.

Pregnant women

Pregnant women can receive Abrysvo at the same time as, or separate to, dTpa, influenza and COVID-19 vaccines as well as Rh (D) Immunoglobulin (Anti-D). Data on co-administration in pregnant women are still emerging, but there are no theoretical concerns.

Studies on co-administration in non-pregnant women showed no safety concerns. There was a small reduction in anti-pertussis antibodies (to filamentous haemagglutinin and pertactin) when Abrysvo and dTpa vaccines were given at the same time.13,16 However, the clinical significance of this is uncertain and no additional dTpa doses are recommended. There were no differences in the immune response to the RSV vaccine.

Infants and children

Infants and children can receive either nirsevimab or palivizumab at the same time, or separate to, routine infant and childhood vaccines and other products (such as oral or intramuscular vitamin K and hepatitis B immunoglobulin).

Co-administration data in infants and children are limited, but studies where nirsevimab was given on the same day as, or within 2 weeks of, routine childhood vaccines showed no difference in safety outcomes compared with when given separately.17 Because monoclonal antibodies target specific antigens, there is unlikely to be any interference with other disease antigens from vaccines or other immunisation products.18

Interchangeability of RSV immunisation products

Abrysvo and Arexvy require only a single dose. No interchangeability is required.

A dose of nirsevimab may replace any remaining doses of palivizumab during that RSV season.

Contraindications and precautions

Contraindications

The only absolute contraindications to RSV vaccines are:

- anaphylaxis after a previous dose of the same RSV vaccine

- anaphylaxis after any component of an RSV vaccine

The only absolute contraindications to RSV monoclonal antibodies are:

- anaphylaxis after a previous dose of the same monoclonal antibody

- anaphylaxis after any component of a monoclonal antibody

Precautions

Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding

Abrysvo is recommended for pregnant women. See Recommendations – Women who are pregnant or breastfeeding.

Pregnant women are not recommended to receive Abrysvo earlier than 28 weeks gestation. This is a precaution while waiting for further data on adverse events of special interest, particularly the risk of preterm birth (see Other adverse events). The advice regarding gestational age at vaccination may be updated as further data become available.

If a woman has inadvertently been given Abrysvo between 24 and <28 weeks, they can be informed that safety data have indicated no statistically significant increase in adverse events compared with women who received the vaccine later in pregnancy.19

Arexvy is not registered for use in pregnant women and should not be given to pregnant women. There is limited data on inadvertent administration in pregnancy demonstrating potential safety concerns.20 If a pregnant woman has inadvertently been given Arexvy, do not give Abrysvo. Arexvy is expected to provide protection against RSV infection to their infant.21 A dose of an RSV monoclonal antibody may be considered for their infant.

See Table. Vaccines that are routinely recommended in pregnancy: inactivated vaccines in Vaccination for women who are planning pregnancy, pregnant or breastfeeding for more details.

People with a history of Guillain–Barré syndrome

There are limited data on the risk of GBS recurrence following RSV vaccination, however, available evidence suggests recurrence of GBS is uncommon in most people with previous GBS. A US retrospective cohort study that followed 550 individuals with a history of GBS found only six (1.1%) had a recurrent diagnosis of GBS from any cause. 22

People with a history of GBS unrelated to vaccination can receive an RSV vaccine, after discussion with their provider about the risks and benefits of receiving an RSV vaccine, taking into consideration their age-related risks, medical risk factors including immunocompromise status, and personal preferences.

People with a history of GBS within 6 weeks of vaccination may have a higher risk of GBS recurrence than if the previous GBS episode was unrelated to vaccination. They should discuss with their provider the risks and benefits of receiving an RSV vaccine.

Adverse events

Abrysvo

Adverse events associated with vaccination of older adults

Among clinical trial participants aged ≥60 years who received Abrysvo:23

- 12% had injection site reactions, compared with 7% who received placebo. Symptoms included pain, redness and swelling at the injection site

- 28% had systemic adverse events, compared with 26% who received placebo. The most common systemic adverse events were fatigue, headache and myalgia

There was no difference in the rates of serious adverse events in participants who received Abrysvo compared with placebo.23

Adverse events associated with vaccination of pregnant women

In pregnant women aged 18-49 years who received Abrysvo between 24 and 36 weeks gestation:24,25

- 32–43% had injection site reactions, compared with 10–14% who received placebo. The most common symptom was injection site pain

- 62–63% had systemic adverse events, compared with 60–62% who received placebo. The most common symptom was fatigue

There was no difference in the rates of serious adverse events in pregnant women who received Abrysvo compared with placebo. There was also no difference in the rates of serious adverse events in the infants born to pregnant women who received Abrysvo compared with infants born to women who received placebo.24,25

Rates of preterm birth after vaccination are being monitored (See Other adverse events of special interest (AESIs).

Arexvy

Among clinical trial participants aged ≥50 years who received Arexvy, pain was the most common injection site reaction, reported by 61% of participants aged ≥60 years (compared with 9% who received placebo)25 and 75% of participants aged 50–59 years (compared with 14% who received placebo).27 Other injection site symptoms included redness and swelling.26,27

The most common systemic reaction was fatigue, reported by 34% of participants of participants aged ≥60 years (compared with 16% who received placebo)26 and 36% of participants aged 50-59 years (compared with 19% who received placebo).27 Other systemic adverse events were myalgia and headache.26,27

There was no difference in the rates of serious adverse events in participants who received Arexvy compared with placebo.26,27

Nirsevimab

No difference in the rates of any adverse events or serious adverse events was seen in clinical trial participants aged from birth to <24 months who received nirsevimab compared with placebo or palivizumab.17,28

Palivizumab

In clinical trial participants aged ≤2 years with haemodynamically significant congenital heart disease, no difference in the rates of any adverse events was seen in those who received palivizumab compared with placebo. The rate of any serious adverse events was significantly lower in those who received palivizumab compared with placebo (p < 0.005).29

Adverse events of special interest (AESIs)

A very small number of AESIs (adverse events of special interest) were reported among trial participants aged ≥60 years who received Abrysvo or Arexvy. These included autoimmune inflammatory neurologic conditions such as GBS (Guillain–Barré syndrome), and atrial fibrillation.30

It was difficult to determine whether the RSV vaccine caused the AESIs because:

- the number of AESIs reported in the studies were small

- some of the studies had no placebo comparator

- some of the studies involved co-administration of RSV vaccine with other vaccines

This means that establishing causality directly to the RSV vaccine was not possible.

Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS)

Clinical trials are not statistically powered to detect rare serious adverse events, so clarification of whether these events occur at higher rates in vaccinated people than the general population requires large post-marketing surveillance studies. Early analysis of post-market surveillance data from the United States and United Kingdom in adults aged ≥60 years suggests that GBS may occur at higher rates than expected after vaccination.31-34 Observed rates of excess cases differ for Abrysvo and Arexvy. For Abrysvo a rate of 9–18 excess GBS cases per million doses within 1–42 days after vaccination has been seen, whereas for Arexvy, a rate of 5–7 excess GBS cases per million doses within 1–42 days after vaccination has been seen. These are both higher compared with an expected rate of 2 GBS cases per million doses. The TGA has issued advice regarding the low risk of GBS following vaccination and the product information for both vaccines has been updated to list GBS as a rare AEFI. GBS remains very rare, and these findings require ongoing analyses and monitoring.

Other adverse events of special interest (AESIs)

A clinical trial of a discontinued candidate GSK RSV maternal vaccine showed an imbalance in the number of preterm births and neonatal deaths in the vaccinated group of pregnant women compared with control pregnant women groups in low- and middle-income countries.21 Because of this, preterm births among pregnant women who received any RSV vaccine are being actively monitored. There was no conclusive evidence of a significant difference in preterm births in the Abrysvo trials and no imbalance was observed in a phase 3 trial of another discontinued maternal RSV vaccine candidate. But, as a precaution, the recommended lower gestational age of vaccination for Abrysvo is 28 weeks. Early studies of the risk of preterm birth in women vaccinated with Abrysvo between 32 and 36 weeks has not shown an increase in preterm birth compared to unvaccinated women.32

Nature of the disease

RSV is a single-stranded RNA orthopneumovirus. RSV strains can be classified into 2 major groups: RSV A and RSV B. Strains from both groups can co-circulate each season.36

Pathogenesis

RSV has an incubation period of 2–8 days.

RSV infects cells lining the respiratory tract, including the small airways within the lung. Infected respiratory cells eventually die, causing an increase in mucus and small airway obstruction. This presents as lower respiratory tract infection.

Severity of infection may be affected by very young or very old age, the presence of certain medical conditions (see Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in adults, and Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children), host immune response, and viral factors.

Previous natural infection does not confer longstanding immunity and reinfection is common. Maternally derived antibody from vaccination or previous infection appears to reduce the risk of infection in young infants during the first few months of life.37

Transmission

RSV is spread in respiratory secretions by:

- contact with infected surfaces, and then transferred into the eyes or respiratory tract

- inhaling virus particles via aerosols

Viral shedding typically occurs for 7–10 days, but can continue for up to 30 days.

Clinical features

Primary infection with RSV, often seen in infants and young children aged 0–2 years, is generally more severe than subsequent infections at older ages.

Symptoms of RSV

RSV may present initially as an acute upper respiratory infection with:

- nasal congestion and discharge

- cough

- scratchy or sore throat

- fever

- otitis media

It may then progress to lower respiratory tract infection, which can present differently depending on age. Approximately 30–71% of infants and young children present with lower respiratory tract infection as part of the primary infection.36

Symptoms of lower respiratory tract infection in infants and children

Infected infants often present with bronchiolitis or pneumonia characterised by:

- respiratory difficulties, with fast, laboured breathing

- wheezing

- reduced oxygen levels on saturation monitoring

- poor feeding

Older children can present with recurrence of infection, although it is less likely to progress to lower respiratory tract infection than for infants. Lower respiratory tract infection in this age group often causes wheezing and is generally milder than that seen with primary infection. RSV illness typically lasts 3–10 days in children.

Symptoms of RSV in adults

In adults, RSV typically causes an upper respiratory tract infection similar to influenza and other respiratory viruses. Typical upper respiratory tract infection symptoms are present, but RSV causes more frequent respiratory wheezing, earache and sinus pain than other viruses.35

Lower respiratory tract infection can occur in adults and is associated with signs and symptoms of breathing difficulty. Bacterial co-infection is seen in approximately 30% of hospitalised patients.38

Complications of RSV

In infants, apnoea or worsening oxygenation can complicate acute RSV infection. Secondary bacterial infection is relatively uncommon.

Recurrent wheezing has been commonly reported in later childhood after a diagnosis of RSV bronchiolitis in infancy. Whether severe RSV infection is causative or simply an early marker unmasking this condition remains unclear.

At all ages, worsening lower respiratory tract infection with RSV can require intensive care unit admission for respiratory support, including non-invasive or invasive mechanical ventilation.

Deaths are uncommon in immunocompetent people but can occur at the extremes of age, such as young infants or older people with frailty. However, the mortality rate associated with RSV disease can be up to 33% in people who are severely immunocompromised, such as haematopoietic stem cell transplant recipients.39

People at risk of severe RSV disease

Risk factors for severe RSV disease in infants are outlined in Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in infants and young children. Some healthy children will also develop severe disease and need hospitalisation. It is difficult to predict which children may require hospitalisation.

Risk factors for severe RSV disease in adults are outlined in Table. Conditions associated with increased risk of severe RSV disease in adults.

Epidemiology

RSV is a leading cause of lower respiratory tract infection, particularly in infants and older people. Almost all children experience RSV infection within the first 2 years of life.36 People at increased risk of RSV infection include preterm infants, people with certain medical conditions, and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

RSV activity varies and is primarily climate-driven. Seasonal outbreaks in most temperate regions in Australia occur during autumn and winter, usually between April and September. The season peaks during June and July,7 often preceding the influenza season.40 In tropical regions, RSV seasonality can be less pronounced and may coincide with rainy seasons.40-43 RSV subtypes A and B co-circulate, but one may be dominant and this may change from year to year.44

RSV disease burden in Australia

Children aged <5 years predominantly account for RSV-associated hospitalisations, with the highest rate in infants during the first few months of life (approximately 4000 per 100,000 population aged 0–2 months, based on RSV-specific coded hospitalisations between 2016-2019). RSV-associated hospitalisation rates generally decline starting in early childhood, and begin to steadily increase in adults from the 50–65-year age cohort.7,45

Among young children, RSV causes a disproportionately high disease burden, particularly in those born preterm. In children aged <5 years, one study showed that those born at <28 weeks gestation have a hospitalisation rate approximately 8 times higher than the overall rate, and those born at 28–31 weeks gestation have a hospitalisation rate approximately 5 times higher. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children also have approximately 2 times higher RSV hospitalisation rates compared with non-Indigenous children.7,8,46

There are limited data on RSV disease burden in Australian older adults. Available data show a 20-fold increase in RSV-associated hospitalisation rates in adults aged ≥65 years between 2006 and 2015 compared with other adults. This is mostly attributable to increased testing and recognition of RSV in the older adult population. The burden of disease in Australian adults is likely underestimated due to infrequent testing in previous years, which is now increasing. To adjust for this possible underestimation, a study that modelled Australian RSV-attributable hospitalisations in adults aged ≥75 years showed the hospitalisation rate to be 256 per 100,000.45

During the COVID-19 pandemic, RSV activity substantially declined and seasonality47,48 was disrupted. However, RSV activity since the 2022–23 season in the Northern Hemisphere and 2023 season in Australia suggests a return towards a pre-pandemic seasonal pattern.49

Vaccine information

Both Arexvy and Abrysvo are protein subunit vaccines that target the prefusion configuration of the RSV F protein, which is relatively conserved among different strains of RSV.

Arexvy codes for a single prefusion F protein, which targets both RSV A and B strains, and contains the AS01E adjuvant. Abrysvo is an unadjuvanted bivalent vaccine containing prefusion F protein from both RSV A and B strains.

For both Arexvy and Abrysvo, vaccination with a single dose of RSV vaccine in clinical trials showed moderate to high efficacy in preventing RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease among older adults during a single RSV season. Protection also extended to a 2nd season.

Abrysvo

Vaccine efficacy in older adults

In a large ongoing clinical trial, adults ≥60 years who received Abrysvo were 89% less likely to have an RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection and 85% less likely to have a medically attended RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection.23,30

Duration of immunity in older adults

After a single dose of Abrysvo, high vaccine efficacy (89%) has been shown through 1 complete RSV season in the Northern and Southern Hemispheres (up to 14 months after vaccination).23,30 Vaccine efficacy of 84% has been shown through 2 RSV seasons for Northern Hemisphere participants (up to 16 months following vaccination, with a mean follow-up of 12 months).30 Vaccine efficacy during the 2nd RSV season after a single dose given before the 1st season was 79%.

Currently, there is not enough evidence to determine the need for revaccination.

Vaccine efficacy in infants of vaccinated pregnant women

Abrysvo is given to pregnant women to protect newborn infants against severe RSV disease by passive immunisation. For infants born to mothers who received Abrysvo, a clinical trial found vaccine efficacy of 57% against hospitalisation for RSV disease for up to 6 months. The trial also found vaccine efficacy of 70% in these infants against severe medically attended RSV-confirmed lower respiratory tract infection in their first 6 months of life.25

Although it is also likely that Abrysvo will protect pregnant women against RSV disease, no data are available on this outcome.

Duration of immunity in infants of vaccinated pregnant women

For infants born to mothers who were vaccinated with Abrysvo, protection against hospitalisation and against severe medically attended RSV-confirmed lower respiratory tract infection beyond the first 6 months of life is significantly reduced. Vaccine efficacy for RSV-confirmed hospitalisations could not be estimated in the clinical trials beyond 6 months. For severe medically attended RSV-confirmed lower respiratory tract infection, no protection was observed between 6 and 12 months.25

No data are available on the duration of antibodies in women who received Abrysvo.

Arexvy

Vaccine efficacy in older adults

In a large clinical trial, adults aged ≥60 years who received Arexvy were 83% less likely to have RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease and 94% less likely to have severe RSV-associated lower respiratory tract disease during the 1st RSV season after vaccination.26

There is no efficacy data in adults aged 50–59 years with medical conditions, but a clinical trial showed that vaccination with Arexvy resulted in an equivalent level of neutralising antibodies compared to adults aged ≥60 years (in whom there are efficacy data) suggesting that equivalent protection was likely.26

Duration of immunity in older adults

After 1 dose of Arexvy, vaccine efficacy of 83% against lower respiratory tract disease was shown during the 1st complete RSV season in the Northern Hemisphere (up to 10 months after vaccination,23,30median of 6.7 months),25 and more moderate vaccine efficacy (67%) was seen through 2 complete RSV seasons (up to a median follow-up of 17.8 months).50 Data on vaccine efficacy during the 2nd season alone after a single dose (administered before the 1st RSV season) was 56% (median follow up of 6.4 months).50

Vaccine efficacy against severe disease after 1 dose of Arexvy was 94% during the 1st complete RSV season in the Northern Hemisphere (up to 10 months after vaccination,23,30 median of 6.7 months).26 Vaccine efficacy was 79% through 2 complete RSV seasons (median follow-up of 17.8 months),50 and efficacy of 64% was shown during the 2nd season alone against severe disease (median follow up of 6.4 months50 during season 2).

Currently, there is not enough evidence to determine the need for revaccination.

Monoclonal antibody information

Both nirsevimab and palivizumab are recombinant human immunoglobulin G1 kappa (IgG1ĸ) monoclonal antibodies. They target the RSV fusion protein (F protein), but nirsevimab binds to a different antigenic site and has a modification to the Fc region that extends its half-life, making it a long-acting monoclonal antibody.51,52 They provide protection against both the RSV A and B strains.

Nirsevimab

Efficacy and effectiveness in infants and children

A clinical trial of infants aged <12 months who were born at term or late preterm (≥35 weeks gestation) showed efficacy of 77% against both RSV hospitalisation and very severe medically attended RSV-associated lower respiratory tract infection for up to 150 days after immunisation.28

Effectiveness data from Spain, France, and the US showed a 70% to 90% reduction in the incidence of RSV-related lower respiratory tract infection hospitalisation, among infants during their first RSV season. In the same studies, there was a 67% to 92% reduction in the incidence of RSV-related ICU admission among these infants, with the observation period spanning 57–150 days.53-62 The reported nirsevimab coverage varied across studies, ranging from 21% to 90%.

Duration of immunity in infants and children

Data on the efficacy of nirsevimab are only available up to 150 days after a single dose. Although it is expected to protect infants for up to 8 months, these data are not yet publicly available.17

Palivizumab

Efficacy and effectiveness in infants and children

A systematic review of the clinical trials for palivizumab in preterm infants or infants aged <2 years with a risk condition showed a pooled relative risk reduction of 51% in RSV-associated hospitalisations and 50% for intensive care unit admissions compared with placebo.63

Data from Western Australia showed 74% lower incidence of RSV infection after any dose of palivizumab compared with no dose46 in high-risk infants aged <2 years.

Duration of immunity in infants and children

Palivizumab is a short-acting monoclonal antibody and requires monthly injections to maintain protection.

Transporting, storing and handling vaccines

Transport according to National Vaccine Storage Guidelines: Strive for 5.64 Store at +2°C to +8°C. Do not freeze. Protect from light.

Abrysvo and Arexvy must be reconstituted. Add the entire contents of the syringe into the vial. Gently swirl until powder is completely dissolved. Do not shake vigorously. Reconstitute immediately after taking the vaccine out of the refrigerator. After reconstitution, administer immediately or store in the refrigerator (+2°C to +8°C) or at room temperature (up to 30°C for Abrysvo or up to 25°C for Arexvy) and use within 4 hours. If it is not used within 4 hours, reconstituted vaccine must be discarded.

Nirsevimab and palivizumab must not be shaken.

Nirsevimab comes as a prefilled syringe. It may be kept at room temperature (store below 25°C) for a maximum of 8 hours. After removal from the refrigerator, nirsevimab must be used within 8 hours or discarded.

Palivizumab comes as a single use vial and should be stored in the refrigerator (+2°C to +8°C). It should be administered immediately after drawing the dose into the syringe.

Public health management

RSV is a notifiable disease in all states and territories in Australia.

State and territory public health authorities can provide advice about the public health management of RSV, including management of cases and contacts.

Variations from product information

Abrysvo

The product information for Abrysvo states it is not for active immunisation in children.

The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) recommends that pregnant women of any age receive the vaccine, including those aged <18 years.

The product information for Abrysvo states the gestational age for vaccination of pregnant women is 24–36 weeks.

The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) recommends that pregnant women receive the vaccine from 28 weeks. ATAGI recommends that if a pregnant woman inadvertently receives the vaccine earlier than 28 weeks gestation, a repeat dose during the same pregnancy is not needed. If pregnant women are not vaccinated before 36 weeks gestation, they can and should receive the vaccine as soon as possible. However, if it is given less than 2 weeks before giving birth, the newborn will not be adequately protected.

Beyfortus (nirsevimab)

The product information for Beyfortus states that the preferred site for administration is the anterolateral aspect of the thigh.

The Australian Technical Advisory Group on Immunisation (ATAGI) recommends that children aged ≥12 months can be given Beyfortus in the deltoid muscle.

The product information for Beyfortus states that the immunisation product is for use in infants born during or entering their first RSV season and children ≤24 months with risk conditions for severe RSV disease through their 2nd RSV season.

ATAGI recommends that Beyfortus also be used for children ≥8 to 24 months of age who are at risk of severe RSV disease entering their third RSV season.

References

- Kong KL, Krishnaswamy S, Giles ML. Maternal vaccinations. Aust J Gen Pract 2020;49:630-5.

- Lively JY, Curns AT, Weinberg GA, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated outpatient visits among children younger than 24 months. Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society 2019;8:284-6.

- Forster J, Ihorst G, Rieger CH, et al. Prospective population-based study of viral lower respiratory tract infections in children under 3 years of age (the PRI.DE study). European Journal of Pediatrics 2004;163:709-16.

- Hall CB, Weinberg GA, Iwane MK, et al. The burden of respiratory syncytial virus infection in young children. New England Journal of Medicine 2009;360:588-98.

- Moore HC, de Klerk N, Keil AD, et al. Use of data linkage to investigate the aetiology of acute lower respiratory infection hospitalisations in children. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 2012;48:520-8.

- Suh M, Movva N, Jiang X, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus is the leading cause of United States infant hospitalizations, 2009-2019: a study of the national (nationwide) inpatient sample. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022;226:S154-s63.

- Saravanos GL, Sheel M, Homaira N, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalisations in Australia, 2006-2015. Medical Journal of Australia 2019;210:447-53.

- Homaira N, Oei JL, Mallitt KA, et al. High burden of RSV hospitalization in very young children: a data linkage study. Epidemiology and Infection 2016;144:1612-21.

- Wilkins D, Wählby Hamrén U, Chang Y, et al. RSV neutralizing antibodies following Nirsevimab and Palivizumab dosing. Pediatrics 2024;154.

- The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne. Palivizumab for at-risk patients. 2024. (Accessed 13 June 2024). https://www.rch.org.au/rchcpg/hospital_clinical_guideline_index/Paliviz…

- Bolisetty S, Osborn D. Palivizunab. 2020. (Accessed 13 June 2024). https://www.seslhd.health.nsw.gov.au/sites/default/files/groups/Royal_H…

- Friedland L. GSK’s RSVPreF3 OA vaccine (AREXVY) : AREXVY was approved by FDA on May 3, 2023, and is indicated for the prevention of LRTD disease caused by RSV in adults 60 and older, as a single dose. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2023. (Accessed 3/3/2024). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/129993

- Athan E, Baber J, Quan K, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of bivalent RSVpreF vaccine coadministered with seasonal inactivated influenza vaccine in older adults. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2024;78:1360-8.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). RSVpreF older adults : clinical development program updates. 2023. (Accessed 13 June 2024). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/129992

- Chandler R, Montenegro N, Llorach C, et al. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of AS01E-adjuvanted RSV prefusion F Protein-based candidate vaccine (RSVPreF3 OA) when co-administered with a seasonal quadrivalent influenza vaccine in older adults: results of a phase 3, open-label, randomized controlled trial. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2024.

- Peterson JT, Zareba AM, Fitz-Patrick D, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F vaccine when coadministered with a tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis vaccine. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2022;225:2077-86.

- Public Health Agency of Canada. An Advisory Committee Statement (ACS) National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI): Statement on the prevention of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) disease in infants. 2024. (Accessed 13 June 2024). https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/phac-aspc/documents/services/publicat…-virus-disease-infants/naci-statement-2024-05-17.pdf

- Esposito S, Abu-Raya B, Bonanni P, et al. Coadministration of anti-viral monoclonal antibodies with routine pediatric vaccines and implications for Nirsevimab use: a white paper. Frontiers in immunology 2021;12:708939.

- ClinicalTrials.gov. A trial to evaluate the efficacy and safety of RSVpreF in infants born to women vaccinated during pregnancy. 2024. (Accessed 13 June 2024). https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT04424316

- Moro PL, Gallego R, Scheffey A, et al. Administration of the GSK respiratory syncytial virus vaccine to pregnant persons in error. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2024;143:704-6.

- Dieussaert I, Hyung Kim J, Luik S, et al. RSV prefusion F protein-based maternal vaccine - preterm birth and other outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine 2024;390:1009-21.

- Baxter R, Lewis N, Bakshi N, et al. Recurrent Guillain-Barre syndrome following vaccination. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2012;54:800-4.

- Walsh EE, Pérez Marc G, Zareba AM, et al. Efficacy and safety of a bivalent RSV prefusion F vaccine in older adults. New England Journal of Medicine 2023;388:1465-77.

- National Institutes of Health. A phase 2B placebo-controlled, randomized study of a respiratory syncytial virus (rsv) vaccine in pregnant women. 2022. (Accessed 13 June 2024). https://classic.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/results/NCT04032093?view=re…

- Kampmann B, Madhi SA, Munjal I, et al. Bivalent prefusion F vaccine in pregnancy to prevent RSV illness in infants. New England Journal of Medicine 2023;388:1451-64.

- Papi A, Ison MG, Langley JM, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine in older adults. New England Journal of Medicine 2023;388:595-608.

- Ferguson M, Schwarz TF, Núñez SA, et al. Noninferior Immunogenicity and Consistent Safety of Respiratory Syncytial Virus Prefusion F Protein Vaccine in Adults 50-59 Years Compared to ≥60 Years of Age. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2024;79:1074-84.

- Muller WJ, Madhi SA, Seoane Nuñez B, et al. Nirsevimab for prevention of RSV in term and late-preterm infants. New England Journal of Medicine 2023;388:1533-4.

- Feltes TF, Cabalka AK, Meissner HC, et al. Palivizumab prophylaxis reduces hospitalization due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children with hemodynamically significant congenital heart disease. Journal of Pediatrics 2003;143:532-40.

- Melgar M, Britton A, Roper LE, et al. Use of respiratory syncytial virus vaccines in older adults: Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices - United States, 2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2023;72:793-801.

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Evaluation of Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) following respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccination among adults 65 years and older. Washington, DC 2024. (Accessed 13 April 2025). https://www.cdc.gov/acip/downloads/slides-2024-06-26-28/06-RSV-Adult-Ll…

- Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Post-licensure safety monitoring of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines in adults aged ≥60 years. 2024. (Accessed 13 June 2024). https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2024-02-28-…

- Fry SE, Terebuh P, Kaelber DC, Xu R, Davis PB. Effectiveness and safety of respiratory syncytial virus vaccine for US adults aged 60 years or older. JAMA Netw Open 2025;8:e258322.

- GOV.UK. Abrysvo▼ (Pfizer RSV vaccine) and Arexvy▼ (GSK RSV vaccine): be alert to a small risk of Guillain-Barré syndrome following vaccination in older adults. United Kingdom: GOV.UK; 2025. (Accessed 30 October 2025 ). https://www.gov.uk/drug-safety-uapdate/abrysvov-pfizer-rsv-vaccine-and-…

- Son M, Riley LE, Staniczenko AP, et al. Nonadjuvanted bivalent respiratory syncytial virus vaccination and perinatal outcomes. JAMA Netw Open 2024;7:e2419268.

- Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases Elsevier; 2020.

- Buchwald AG, Graham BS, Traore A, et al. Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) neutralizing antibodies at birth predict protection from RSV illness in infants in the first 3 months of life. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2021;73:e4421-e7.

- Falsey AR, Becker KL, Swinburne AJ, et al. Bacterial complications of respiratory tract viral illness: a comprehensive evaluation. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2013;208:432-41.

- Renaud C, Campbell AP. Changing epidemiology of respiratory viral infections in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients and solid organ transplant recipients. Curr Opin Infect Dis 2011;24:333-43.

- Price OH, Sullivan SG, Sutterby C, Druce J, Carville KS. Using routine testing data to understand circulation patterns of influenza A, respiratory syncytial virus and other respiratory viruses in Victoria, Australia. Epidemiology and Infection 2019;147:e221.

- Minney-Smith CA, Foley DA, Sikazwe CT, Levy A, Smith DW. The seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus in Western Australia prior to implementation of SARS-CoV-2 non-pharmaceutical interventions. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2023;17:e13117.

- O'Grady KA, Torzillo PJ, Chang AB. Hospitalisation of Indigenous children in the Northern Territory for lower respiratory illness in the first year of life. Medical Journal of Australia 2010;192:586-90.

- Paynter S, Ware RS, Sly PD, Weinstein P, Williams G. Respiratory syncytial virus seasonality in tropical Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2015;39:8-10.

- Saravanos GL, Ramos I, Britton PN, Wood NJ. Respiratory syncytial virus subtype circulation and associated disease severity at an Australian paediatric referral hospital, 2014-2018. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 2021;57:1190-5.

- Nazareno AL, Muscatello DJ, Turner RM, et al. Modelled estimates of hospitalisations attributable to respiratory syncytial virus and influenza in Australia, 2009-2017. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2022;16:1082-90.

- Moore HC, Lim FJ, Fathima P, et al. Assessing the burden of laboratory-confirmed respiratory syncytial virus infection in a population vohort of Australian children through record linkage. Journal of Infectious Diseases 2020;222:92-101.

- Eden JS, Sikazwe C, Xie R, et al. Off-season RSV epidemics in Australia after easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Nat Commun 2022;13:2884.

- Saravanos GL, Hu N, Homaira N, et al. RSV epidemiology in Australia before and during COVID-19. Pediatrics 2022;149.

- Hamid S, Winn A, Parikh R, et al. Seasonality of respiratory syncytial virus - United States, 2017-2023. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2023;72:355-61.

- Ison MG, Papi A, Athan E, et al. Efficacy and safety of respiratory syncytial virus prefusion F protein vaccine (RSVPreF3 OA) in older adults over 2 RSV seasons. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2024.

- Simões EAF, Madhi SA, Muller WJ, et al. Efficacy of nirsevimab against respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections in preterm and term infants, and pharmacokinetic extrapolation to infants with congenital heart disease and chronic lung disease: a pooled analysis of randomised controlled trials. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health 2023;7:180-9.

- Hashimoto K, Hosoya M. Neutralizing epitopes of RSV and palivizumab resistance in Japan. Fukushima Journal of Medical Science 2017;63:127-34.

- Ares-Gómez S, Mallah N, Santiago-Pérez MI, et al. Effectiveness and impact of universal prophylaxis with nirsevimab in infants against hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus in Galicia, Spain: initial results of a population-based longitudinal study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases 2024.

- Assad Z, Romain AS, Aupiais C, et al. Nirsevimab and hospitalization for RSV bronchiolitis. New England Journal of Medicine 2024;391:144-54.

- Barbas Del Buey JF, Íñigo Martínez J, Gutiérrez Rodríguez M, et al. The effectiveness of nirsevimab in reducing the burden of disease due to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) infection over time in the Madrid region (Spain): a prospective population-based cohort study. Front Public Health 2024;12:1441786.

- López-Lacort M, Muñoz-Quiles C, Mira-Iglesias A, et al. Early estimates of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis effectiveness against hospital admission for respiratory syncytial virus lower respiratory tract infections in infants, Spain, October 2023 to January 2024. Euro Surveill 2024;29.

- Ezpeleta G, Navascués A, Viguria N, et al. Effectiveness of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis administered at birth to prevent infant hospitalisation for respiratory syncytial virus infection: A population-based cohort study. Vaccines (Basel) 2024;12.

- Agüera M, Soler-Garcia A, Alejandre C, et al. Nirsevimab immunization's real-world effectiveness in preventing severe bronchiolitis: a test-negative case-control study. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology 2024;35:e14175.

- Coma E, Martinez-Marcos M, Hermosilla E, et al. Effectiveness of nirsevimab immunoprophylaxis against respiratory syncytial virus-related outcomes in hospital and primary care settings: a retrospective cohort study in infants in Catalonia (Spain). Archives of Disease in Childhood 2024;109:736-41.

- Carbajal R, Boelle PY, Pham A, et al. Real-world effectiveness of nirsevimab immunisation against bronchiolitis in infants: a case-control study in Paris, France. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health 2024;8:730-9.

- Moline HL, Tannis A, Toepfer AP, et al. Early estimate of nirsevimab effectiveness for prevention of respiratory syncytial virus-associated hospitalization among infants entering their first respiratory syncytial virus season - new Vaccine Surveillance Network, October 2023-February 2024. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 2024;73:209-14.

- Paireau J, Durand C, Raimbault S, et al. Nirsevimab effectiveness against cases of respiratory syncytial virus bronchiolitis hospitalised in paediatric intensive care units in France, September 2023-January 2024. Influenza Other Respir Viruses 2024;18:e13311.

- Andabaka T, Nickerson JW, Rojas‐Reyes MX, et al. Monoclonal antibody for reducing the risk of respiratory syncytial virus infection in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2013.

- Australian Government Department of Health and Aged Care. National vaccine storage guidelines: Strive for 5. 3rd ed. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Health and Ageing; 2019. https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/national-vaccine-stora…

Page history

Addition of guidance for vaccination of individuals with a history of GBS unrelated to previous vaccination and individuals with a history of GBS following previous vaccination.

Addition of epidemiological evidence on rates of GBS after RSV vaccination.

Updates to reflect the age extension of Arexvy among adults aged 50–59 years with medical risk conditions that increase the risk of severe RSV disease. Updates to wording around the upper gestational age for the administration of Abrysvo.

Updates to reflect the new National RSV Mother & Infant Protection Program (RSV-MIPP).

New RSV chapter has been developed to provide information on recommendations for use of RSV immunisation products.

Recommendations include use of RSV vaccines in adults and pregnant women and use of long-acting RSV monoclonal antibodies in infants and young children.

Addition of guidance for vaccination of individuals with a history of GBS unrelated to previous vaccination and individuals with a history of GBS following previous vaccination.

Addition of epidemiological evidence on rates of GBS after RSV vaccination.

Updates to reflect the age extension of Arexvy among adults aged 50–59 years with medical risk conditions that increase the risk of severe RSV disease. Updates to wording around the upper gestational age for the administration of Abrysvo.

Updates to reflect the new National RSV Mother & Infant Protection Program (RSV-MIPP).

New RSV chapter has been developed to provide information on recommendations for use of RSV immunisation products.

Recommendations include use of RSV vaccines in adults and pregnant women and use of long-acting RSV monoclonal antibodies in infants and young children.